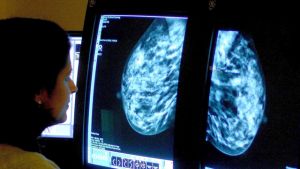

Mammography, properly conducted, is the best tool for early detection of breast cancer. But this special report from NOW With Bill Moyers, produced with The New York Times, considered what happens when a woman opts for the test, and the person reading it isn’t up to the job.

A year-long investigation by the Times found that many of the 20,000 doctors who read mammograms lack the skills to interpret them correctly. What can a woman do to protect herself?

TRANSCRIPT

MOYERS: Welcome to NOW.

A close friend and colleague of mine is fighting breast cancer. The chemotherapy is behind her, and her beautiful red hair is sprouting again under her baseball cap. We’ve all come to like that cap. It matches the spirit of a woman who’s determined not to be called out on a low-curve ball if she can help it.

Two hundred thousand women are diagnosed with breast cancer every year; 40,000 of them don’t survive. Mammography, properly conducted, is said to be still the best tool for early detection of cancer. But what happens if a woman opts for the test and the person reading it isn’t up to the job? How is she even to know?

That’s the subject of our special report produced with THE NEW YORK TIMES. A year-long investigation by the “Times,” published this week, found that many of the 20,000 doctors who read mammograms lack the necessary skills for the job. Here’s our report, prepared by “Times” correspondent Lowell Bergman, reporter Michael Moss, and producer David Rummel.

LOWELL BERGMAN: Trisha Edgerton is a medical physicist by training, a mammography expert. So when she went in for her mammogram at the age of 38, she did her homework, inspecting the breast x-ray machine before she had her screening.

TRISHA EDGERTON: I actually felt like I had an insider’s view. I had the, you know, the goods on where I could go to get my mammogram, so I chose a facility that I knew was excellent. The mammogram was read as normal, and I didn’t give it another thought, and approximately five months later I found a mass in my breast, so I had the films reread, and they came back positive. And the problem here was that what I did not count on was what I call “radiologist roulette.”

BERGMAN: What did you call it?

EDGERTON: Radiologist roulette. That is that any day that your films are being read and they come across the radiologist viewbox, it depends on which radiologist in that firm happens to be sitting there. The radiologist was an excellent radiologist, unfortunately, he was an excellent neuroradiologist.

BERGMAN: He was a specialist in the brain, not the breast. He missed her tumor. That’s because radiologists are not required to be specialists in mammography to read a mammogram. When she took her x-ray to a breast specialist, he called it an across-the-room tumor.

EDGERTON: It stood out so much, that he could have read it from across the room.

BERGMAN: It turns out that Trisha Edgerton’s experience is not an isolated case. THE NEW YORK TIMES has completed a year-long examination of the state of mammography screening in this country, based on hundreds of interviews with doctors, experts and regulators. NEW YORK TIMES reporter Michael Moss discovered that many of the 20,000 American doctors who read mammograms lack the skill needed to do so effectively, and the patients have no way to find out who is good and who is not.

MICHAEL MOSS: Women are told that doctors miss between 10% to 15% of cancers, but the first extensive studies involving doctors in two states show they’re missing nearly 30% on average, and in some cases, nearly 40%.

BERGMAN: The result is that thousands of breast cancer cases may not be detected early when treatment is more effective, and more lives can be saved.

MOSS: What we found in our examination is that mammography in this country is very much a two-tier system, a few places are pushing far beyond the federal rules to improve the accuracy of their mammograms, but many others are doing just the bare minimum required by the federal government.

BERGMAN: The problem isn’t the mammograms themselves, it’s the doctors who read them. The federal government requires that a radiologist screen 480 breast x-rays a year to qualify as a mammographer, but this is far below what many experts believe is needed for proficiency. And American women can’t tell which doctors are proficient because the government does not monitor their performance. There is one location that does, and it may be a model for the rest of the country — Kaiser Permanente, a non-profit H.M.O. in Denver, Colorado.

DR. DEBORAH SHAW: You can see those little fingers of cancer extending out from the masses here.

BERGMAN: you’re looking at breast cancer on a breast x-ray, a mammogram. Spotting a tumor is an art form. Amidst the shadows and the swirls of the image, the age of the patient, and the varying density of the breast tissue, finding cancer is a challenge for the radiologist.

SHAW: These are all different patients. You can see how each mammogram is as individual as a person, they’re all different. In this particular case, this lady had a vague area of asymmetry.

BERGMAN: Dr. Deborah Shaw is Chief of Mammography at Kaiser, a medical detective searching for elusive signs of cancer.

SHAW: What makes this so interesting is looking here — infinitesimal, tiny, tiny, tiny calcifications in this area right here. And a biopsy of this large mass turned out to be a cancer, as well as these tiny calcifications in the right breast. We’re going to roll these out on the rest of the clinics.

BERGMAN: what makes Kaiser so unusual is that these doctors keep score, tracking every tumor found and every one that is missed; then learning from their mistakes.

SHAW: This is a performance-based system. And so we welcome understanding how well we’re performing because this group of people wants to do better.

BERGMAN: Better means finding 80% of the breast cancer they come across in initial mammogram screenings, one of the best detection rates in the nation. Finding cancer sooner means subsequent treatment is more effective.

DR. RICHARD PROPPER: Mass suspicious calcification. Impression negative.

BERGMAN: Dr. Richard Propper works in a darkened viewing room with no distractions, often viewing 100 or more x-rays in one session; nearly 7,000 in the last year. Expertise in mammography requires a special aptitude, but it isn’t just high volume that keeps him sharp. Dr. Propper receives constant feedback on his performance, along with frequent tests of his ability to spot tumors in a stack of specially selected x-rays.

PROPPER: It gives you a reassurance that we all have in the group, that we are doing well, and that we can know for our confidence level and reassurance that the quality of interpretation that we’re doing is excellent.

BERGMAN: Their excellence came only after Kaiser set up their tracking system in 1995. It created unwelcome front-page news in Denver. The system uncovered a senior doctor who was missing many cancers, and then was fired as a result. In all 3,100 of his patients, breast x-rays had to be reevaluated; 259 women were called back for follow-up x-rays; ten had cancer.

ANN VEENSTRA: I was upset and angry that there was a doctor on staff that could take people’s lives so casually.

BERGMAN: Ann Veenstra was one of those called back for a second mammogram. It showed cancer, and she had breast surgery. She says Kaiser’s tracking system saved her life.

VEENSTRA: I trusted that that system would take care of me, and, in fact, it did take care of me in the end. I think it would be good if they could assure their patient that there are people who do double checks. It would be nice if the physicians were open to that.

BERGMAN: If the system in Denver were applied nationally, thousands of breast cancer cases could be detected sooner, saving money and lives. The Kaiser approach includes these steps: tracking cancers found and missed, constant doctor feedback, reading a high volume of mammograms, and frequent testing of doctor skills. But this is not the norm in this country.

Congress tried and failed to address the issue of radiologist skill, when it passed the mammography quality standards act ten years ago. New regulations from the F.D.A. focused on the x-ray machines, image quality, clinic staff and training and education, and quality control backed by inspections and a government- certification program. The changes vastly improved the quality of breast x-rays. But efforts to monitor doctor’s performance, their ability to spot cancers, were defeated. Doctors persuaded the F.D.A. that performance data could be misinterpreted, and that radiologists would stop doing mammograms if they were too closely monitored. In the end, it left American women with no tools to determine whether a doctor was doing a good job.

PAMELA WILCOX, AMERICAN COLLEGE OF RADIOLOGY: The only information that we make public is that the facility is accredited.

BERGMAN: Pam Wilcox oversees the accreditation of mammography clinics for the American College of Radiology, the A.C.R. The A.C.R. is a trade group for radiologists, and it was chosen by the F.D.A. to evaluate the technical quality of the breast x-ray images, and that’s what they focus on, not doctor performance. The head radiologist of a breast care clinic has to select and send in two sets of the best- quality mammograms the clinic can produce to gain accreditation.

LOWELL BERGMAN: But you can’t walk into a clinic and say, “I want to see the record, the American College of Radiology’s assessment of the people who are reading your films.”

PAMELA WILCOX: We don’t look at physicians individually. It’s a facility evaluation.

BERGMAN: One person said to us what it’s like: it’s radiologists’ roulette for women. You take your chances when you walk in; you don’t know how good the people are going to be.

WILCOX: Isn’t that true in every part of medicine, and even, let’s say, the legal profession. You know, you don’t know exactly what you’re getting. You talk to your friends, you ask for a referral. If you have doubts, if a woman has doubts, we need to take responsibility for our healthcare.

TRISHA EDGERTON: This is life and death for many women.

BERGMAN: Trisha Edgerton says the stakes are too high to be left to the patient. She thinks state and federal governments need tougher performance standards for radiologists.

EDGERTON: I believe that there needs to be some regulation regarding these physicians. They are the captains of the ship in mammography, they’re the ones who are responsible for knowing good films.

BERGMAN: Trisha Edgerton, who worked for the California Department of Health Services, was asked to run the state’s mammography accreditation program in 1996, and she was determined to hold the radiologists accountable. Edgerton set up a program that would send doctors back for remedial training after they repeatedly failed to meet the minimum standards set by the F.D.A.

EDGERTON: I had many interesting comments from radiologists when I would call them and say that they needed to do this. I had comments such as, “listen, little lady, I’ve been doing mammography for 20 years,” and I would respond, “if you want to do it for the next 20, this is what you’re going to do.”

BERGMAN: Trisha Edgerton is still disturbed by the worst case she encountered: Los Angeles radiologist Dr. Marvin E. Weiner, who was ordered to take remedial training two times in three years. The last session did not go well. According to this state memorandum, his training instructor told Edgerton’s assistant that, “Dr. Weiner is unable to discern the difference between good and bad mammograms, and is unwilling to provide good mammography services.” The memo went on to add that “Dr. Weiner should retire,” and that “additional training would be ineffective.” Dr. Weiner declined our requests for an on-camera interview, but he did speak briefly on the phone to Michael Moss.

MICHAEL MOSS: Dr. Weiner declined to comment on the instructor’s conclusion. He said, “that’s her opinion, so be it.” But he did say that he thought the entire system that’s in place to scrutinize doctors was unfair. He said some of the rules are too high to meet, impossible to meet even, and that when films are submitted to American College of Radiology, that doctors who read them, themselves, have been flat-out wrong.

BERGMAN: Dr. Weiner screened more than 26,000 women at a Los Angeles clinic. The clinic failed a series of inspections and accreditation reviews, and finally closed. Alice Pride was one of Dr. Weiner’s patients.

BEVERLY DANIELS: She would always call and make her doctor’s appointments when it was time for her x-ray, mammogram, or whatever.

BERGMAN: In 1998, Dr. Weiner read Alice Pride’s annual mammogram as normal. A year later, another doctor found a breast tumor. Alice Pride then sued Dr. Weiner for malpractice. Misread breast x-rays are one of the leading malpractice complaints in this country.

DANIELS: Alice was always concerned about breast cancer because her mother, her grandmother, and she had female cousins that also had breast cancer, and the survival rate… Really there was no survival rate when they got cancer.

BERGMAN: Alice Pride died last fall from breast cancer. Her case was settled; the details are confidential and do not necessarily mean Dr. Weiner was at fault. Meanwhile, Dr. Weiner can still legally read mammograms, and he is still reading them three years after his remedial trainer said he couldn’t tell a good mammogram from a bad one. The California State medical board says it is reviewing the matter.

EDGERTON: There’s a point where you need to inform this individual that they can no longer be responsible for a mammography program; they can no longer read mammograms.

BERGMAN: But Trisha Edgerton says that Dr. Weiner, and others like him, were a source of great frustration, and one of the reasons she finally quit her job three years ago.

EDGERTON: We had ways to catch them, identify them, and there was no repercussions once we did identify them.

DR. DAVID FEIGEL: The practice of medicine is something that’s regulated state by state. There is no F.D.A. Authority to take an action against a medical license.

BERGMAN: Dr. David Feigel oversees the Food and Drug Administration program that governs mammography.So, you’re saying it’s not our department, it’s the state’s.

FEIGEL: It’s a systems approach. We each have different responsibilities. Our responsibility is to make sure that the facilities and the people who operate them are operating them at a high quality and are keeping up with the technology changes.

BERGMAN: No one has questioned that the quality standards of checking the facilities and the machinery and the technology, that that’s all improved. The question is the radiologist.

FEIGEL: If, in fact, we determine that the quality has not been up to standard, we can require that they notify their patients.

BERGMAN: Has the F.D.A. ever fined a clinic?

FEIGEL: Yes, we have. We have the authority to level civil money penalties, and we have done that.

BERGMAN: How many times?

FEIGEL: I think we’ve only done it once. It’s not the first corrective action that we would take against a clinic. The first action that we would take would be to give them a list of things that they need to correct in the clinic and a time frame for doing that. And most clinics, in fact, do make the corrections.

BERGMAN: One out of how many clinics in the country?

FEIGEL: There’s about 10,000 clinics.

BERGMAN: You’re comfortable having any female member of your family walk into any clinic as long as it has accreditation?

FEIGEL: Yes, I am.

EDGERTON: I believe that the F.D.A. Tried to do a lot of things.

BERGMAN: Edgerton says the F.D.A. Publishes a list of clinics that have certification. They wanted to have a list of facilities but in the end it doesn’t make a difference that the radiologist packed up and moved and is now operating under a new name. So there was some good intent there, and unfortunately, the net hasn’t been tight enough to catch those radiologists that are really doing a poor job.

EDGERTON: We’re just going to do the right side, the middle portion.

BERGMAN: So what should a woman do to protect herself, to insure that she gets a good mammogram screening? Trisha Edgerton believes one point is indisputable: annual mammogram screenings beginning at age 40 are still the best tool women have to detect breast cancer. Her advice? Go to a breast x-ray specialist and ask questions.

EDGERTON: Find out who is the main mammographer/physician, who reads the most mammograms, who do they consider their lead interpreting physician, which is a technical term used by F.D.A., find out who that person is, and require, don’t request, require that that is the person who reads your films. Don’t count on what I had, which is radiologist roulette.

MOYERS: Our subject now is God and politics, here and abroad. Listen to this commercial that began running on some 800 radio stations last week.

ANNOUNCER (RADIO AD PAID FOR BY “STAND FOR ISRAEL”): As bombing murderers attack in Israel, innocent people are dying every day. A grandmother killed at a Passover meal, a teenage girl murdered at a bus stop, a baby mutilated in a food market. Victims of terrorism are dying for Israel’s basic right to exist. As Americans, we must take a stand for Israel. As Christians, we are instructed to pray for peace in Jerusalem. According to a recent survey, 62% of evangelical Christians support Israel. As people of faith, as people of God, we must make our voices heard now.

MOYERS: That ad is the work of my next two guests. They’ve launched a new campaign aimed at mobilizing 100,000 churches and one million Christians to stand with Israel. Yechiel Eckstein, a fourth generation rabbi who now lives outside Chicago, is the president of the International Fellowship of Christians and Jews. He co-chairs the campaign is long-time republican activist Ralph Reed. He ran the Christian Coalition for Pat Robertson and now runs his own political consulting firm in Atlanta where he is also chairman of the Georgia Republican Party. Thanks to both of you for joining me.

REED AND ECKSTEIN: Thanks, Bill.

MOYERS: What does it mean in the Arab world when they see Christians and Jews so directly influencing American policy toward Israel?

RALPH REED: Well, fortunately we live in a democracy, Bill, and it’s the right of all people of all faiths, all ethnic backgrounds to mobilize to educate and to encourage people to make their voices heard.

MOYERS: How do you think it’s been taking… What do you think it does to the Arab world when they see that?

REED: Well, I think there is a very significant portion of the Arab world that very much agrees with the fact that we need to have two peoples living side by side in peace, renouncing terror. And that’s what our campaign is really all about. What we’re saying is we respect the right of the Palestinians to have their legitimate aspirations for democracy, for freedom, for hope, and prosperity to be recognized. We want that to be done in a way that doesn’t threaten the right of Israel to exist.

MOYERS: Rabbi, I understand the ad ran on Rush Limbaugh, Dr. Laura Schlesinger, many other conservative talk shows. Why didn’t you appeal to liberal Christians?

ECKSTEIN: Well, we’re focusing on the public at large, and I think that the conservative Christians, firstly…

MOYERS: Public at large? Rush Limbaugh? Dr. Schlesinger? That ad ran, I believe…

ECKSTEIN: WASHINGTON POST, you know, the public at large…

MOYERS: Radio stations…

ECKSTEIN: …Bill Moyers.

ECKSTEIN: We are focused, though. I’ve been working with the evangelical Christian community for 25 years, so if you will, that’s my constituency. At the same time, it has been those people who have really taken the forceful strong stand. It hasn’t come from the liberal community. It’s come from the religious conservative evangelical community that has been taking what we’re doing is simply channeling that, trying to give them a way to do something with that pent-up emotion of solidarity that they have.

MOYERS: Your ad last week in THE NEW YORK TIMES shows Yasser Arafat and Jerry Falwell side by side. Arafat is a repugnant man I think has betrayed the Palestinian cause. But to many of us, Jerry Falwell represents the bigoted Anti- Semitic theocratic dark side of our faith. Why did you choose Jerry Falwell to represent Christians supporting Israel?

ECKSTEIN: Firstly, I would want to question that perception. The perception that he is Anti-Semitic I think, is a wrong perception and an unfair fair one in his case. I think that there have been a lot of stereotypes within the Jewish community, my own Jewish community, and within, if you will, the liberal community…

MOYERS: Right, but why did you choose him?

ECKSTEIN: Because he’s really become a symbol for the public at large of that which many fear and the same way that…

MOYERS: What do you mean? I don’t understand that. Many fear…?

ECKSTEIN: Many fear the quote “Christian Right.” Many within the Jewish… And this ad was directed also towards the Jewish community to essentially rethink who are our true friends and who are our adversaries.

MOYERS: But this is a man who said after 9/11 on your old boss’ show, “I think that Americans got what they deserved when the terrorists attacked the World Trade Center.” And your boss, Pat Robertson, sitting right beside him, said, “Jerry, I agree.” Do you trust a Christian like that?

ECKSTEIN: Firstly, he repudiated those comments, Jerry Falwell. But apart from that, I think that’s simply leaving aside what the concept of the ad, which, in an ad you try to get it across as clearly and as quickly as possible…

MOYERS: But you chose Jerry Falwell to represent American Christians.

ECKSTEIN: Because…

REED: Bill, if I can jump in here, that was the whole point.

MOYERS: Tell me…

REED: The point is we’re not saying that there aren’t going to continue to be disagreements between the Jewish and the Christian community, or for that matter, between liberal and conservative Christians. The point is is that those disagreements can take place between friends and allies on the issue of Israel rather than among adversaries sniping at each other across the barricades of distrust, which…

MOYERS: Did you agree with Pat Robertson and Jerry Falwell when they said we got what we deserved on 9/11?

REED: No, I did not. We are in no way associating ourselves with those views. The only views we’re associating ourselves with are the quotation that appeared in the ad, which said that the United States should stand with Israel and we should sympathize with the Israelis as they seek to protect their homeland.

MOYERS: So theology and politics do not matter? The opinions of your allies do not matter provided they support Israel’s policy?

REED: No, I didn’t say that.

MOYERS: No, I’m not…I know you didn’t, I’m not saying you said it, I’m asking you the question.

REED: No, of course they matter, but the point is this: just as Jews and African Americans who had had decades, if not centuries of pain and distrust that divided them based on all kinds of issues came together during the civil rights movement because they shared a desire for African Americans to have the right to vote; so, too, today Jews and Christians and, yes, liberal and conservative Christians, can come together on an issue that binds them. Why be divided when there is an issue of such crisis proportions that we can come together and unite on? And if we will do that and have a dialogue based on mutual respect rather than fear and suspicion, I am hopeful, Bill, and I know Rabbi Eckstein is, that we’ll then be able to find some common ground on some other issues as well.

MOYERS: In the Johnson administration, the Kennedy administration, in my work as a journalist, I have been a consistent supporter of Israel’s right to exist. I think Israel has a moral right to defend itself. I find the suicide bombings are an atrocity. Yet I was offended, quite frankly, as a Christian, when you took Jerry Falwell and shoved him in my face and in effect said, “Moyers, people like you, we don’t consider you our best allies.”

ECKSTEIN: I think that’s a challenge to people who are on the liberal spectrum of the Christian community. Our position from the International Fellowship of Christians and Jews– and we’ve been working with the evangelical Christian community, for as I said, for a lot of years– has been very simple. Cooperate wherever possible, oppose whenever necessary, and teach and sensitize at all times. So what we’re saying is, “hey, there are going to be areas, like on Israel, where we can cooperate, let’s cooperate. There are going to be issues where we’re going to differ. Let’s differ, but let’s always have a dialogue.”

And if the liberal Christian community is offended by our reaching out to the conservative Christian community for support and solidarity when Israel’s very survival is at stake, and they are not coming to the rescue, if you will, then…

MOYERS: I don’t find… what liberal… I don’t know any liberals who are not defending Israel’s right to exist and who are… Who have condemned the atrocities of the suicide bombings.

ECKSTEIN: There’s a positive, a neutral and a negative. I’m… Let’s say that the liberal Christian community is by and large neutral. Let’s even give it that.

MOYERS: I don’t think they are, I disagree with you on that.

ECKSTEIN: Well, then we’d have to…

MOYERS: What do you mean by neutral?

ECKSTEIN: Well, then we’d have to define what is the survival of Israel that is at stake at this point. There is… Would you suggest that the liberal Christian community’s views are as favorable towards Israel’s right to enter into the territories, to destroy terrorism as the conservative Christian?

MOYERS: You mean, do we… do liberals support the right of settlements in?

ECKSTEIN: No, no. I’m saying when Israel, when the president now allows, seems to allow Israelis to go into fight when the Palestinians themselves are not taking out the roots of terrorism and Israel goes in and…

MOYERS: Israel has the right to defend itself. Many Christians, many Christians…

ECKSTEIN: Then you can be part of our stand for Israel.

MOYERS: Many Christians like Falwell support Israel’s expansion into the West Bank, because it’s part of the… It’s the promised land of Biblical prophecy. Ralph Reed, you’re a Christian. Do you support them? Do you believe that Israel, that Jews have… Should be on the West Bank as part of the Biblical fulfillment of that prophecy?

REED: Well, I have a fairly expansive view of God’s sovereignty, and I do not necessarily associate the promises of God given to the Jews in the Old Testament with a particular political border or a particular nation state. I do believe that… There is an historical connection between the Jews and that land. It has… It was their ancient and historic home, it is where they have returned since 1948, and it is where they are safe and secure.

I agree with what the President said earlier this week where he said they had a right to safe and secure borders. I believe the issue of the exact nature of those borders has to be worked out in negotiations between the Palestinians, the Israelis and other parties.

MOYERS: Do you believe that Jews have a divine right to those settlements? I mean, they invoke God for their sanction. Do you agree with that?

REED: I agree that God made promises to the Jews for that land, yes. But I want to make it clear that the exact borders of a modern state of Israel, and you know this, Bill, you would have disputes among Christians, Protestant, Catholic and Jewish theologians and scholars on this as to whether or not that relates to a specific polity. Do you see what I’m saying?

MOYERS: Mm-hmm. A few weeks ago we did a report on the broadcaston Jewish settlements on the West Bank. These settlers were American Jews who moved to Israel. They’re on a religious mission to plant themselves on the promised land. We’ve done an update, there has been a lot of violence on the West Bank and these settlers have been affected. Let me show you the update we’ve just done and ask you some questions about it.

DAVID RUBIN: During Operation Defensive Shield, the government sent in the army to several of the autonomous cities of the Palestinian Authority and a lot of progress was made, but it has to be put in perspective. There is still danger, there is still risk.

MARK: People are driving less on the roads, we are taking the armored buses more. And unfortunately, we’ve gotten to the situation where people are going out with bulletproof vests. People have not felt safer as of yet.

DAVID RUBIN: Since my son and I were injured in the terrorist attack, we’ve been taking the buses a lot more just to reduce the risk.

MARK: School children are a popular target among the terrorists in the area. School children and people in their regular cars. That’s their favorite.

LISA RUBIN: You worry about your children living here where we live over the Green Line, but I am more worried about my son who is walking around Jerusalem today.

MARK: When the intifada started over a year and a half ago, the people of Israel realized that the violence wasn’t just directed towards those of us who live on the other side of the fence. They realized that the violence was directed at everybody.

LISA RUBIN: People are saying put up a fence, but you could jump over the fence. You know, those who want to blow themselves up to kill more Jewish people are going to blow themselves up and kill more Jewish people whether they are in a fence or outside of a fence.

DAVID RUBIN: All the talk about the settlements being the obstacle to peace are unrealistic. It’s ignoring the main issue; the main issue is that we have a hostile Arab population living in the land of Israel that is hostile to our very presence here.

MARK: If the solution to peace was for us to get up and leave, would I be willing to move? Is an interesting question. If they promised me total peace, total peace– if we were to leave this area, my internal feeling would be it would be ripping my heart out.

DAVID RUBIN: The Arabs, if they’re not willing to live in peace with us, they need to be transferred over the borders. There are 23 Arab states surrounding us. They have a lot of land. They have a lot more land than we do, that’s for sure. When one says to me, “how do you propose to move the populations over the border if they don’t want to go?” I return the question back to them and I say, “what do you propose to do when you’re talking about transferring Jews from the settlements? What if the Jews don’t want to go, and are you morally right in doing so, when all we want to do is live here peacefully?” It’s us or them. It can’t be both. It can’t be both.

MOYERS: That was an update on the piece we did a few weeks ago. And the question that goes out of it is, if any of us– but in particular those settlers– if we believe we have a divine right to be somewhere, doesn’t that make politics impossible? Doesn’t that mean it’s impossible to negotiate when I can claim God’s authority for my behavior? Ralph?

REED: I don’t think so. No, I really don’t. I think, in fact, Israel has already negotiated things away that a significant percentage of their populations believe was their divine right. I think Israel has demonstrated repeatedly during the Oslo process, during the camp David accords, during the peace negotiations with Jordan, that they are prepared to trade land for peace, to negotiate land for peace, if it’s true peace. And I think that it is just simply untrue that those things cannot be negotiated. It is not to say, by the way, that it is not without domestic political ramifications in Israel or that it is without great turmoil within the country. It clearly is.

MOYERS: Isn’t it also a great political benefit to the Republican Party in this country?

REED: I don’t really view it as benefiting one party or…

MOYERS: Isn’t this a campaign? Some of your critics say that this is a campaign to move Jews out of the Democratic Party into the Republican Party.

REED: No, what this is about is this is about encouraging Americans of all faiths and all parties to stand with Israel, and that’s all it’s about.

MOYERS: Rabbi, do you believe those settlers have a divine right to be there?

ECKSTEIN: I would take it a little bit further than Ralph, as a Jew. I believe that Jews have a right– both historical and divine right– to live in Hebron where Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob are buried. I do believe that.

MOYERS: Palestinians are also descendants of Abraham.

ECKSTEIN: They are welcome there. Nobody is kicking them off their land. The question is whether these two peoples can live there. Why should Hebron be Judenrein? No Jews are…

MOYERS: What do you mean…

ECKSTEIN: In other words, no Jews should be allowed to live there. What flag is put up is a political issue. So if you ask me in terms of divine right, I do believe that Jews have a divine and historical right. There were Jews living in Hebron until 1929 after… When they were massacred in the Yeshiva, in the seminary, and the Jews were then kicked out of Hebron. Jews have a right to be there.

Now, is it something when you have political exigencies that should be negotiated, I think everyone including the person on the screen and certainly Prime Minister Sharon is willing to negotiate based on the political exigencies. But I would focus, again, on the fact that bombs… I live now in Jerusalem, too, and bombs are exploding every day almost in the city of Jerusalem. Do Jews have a divine right to be in Jerusalem, a historical right? I believe, yes.

MOYERS: Our time is up, but I thank both you, Ralph Reed, and Rabbi Eckstein, for being with us. Thank you.

ECKSTEIN: Thank you.

REED: Thanks, Bill.

MOYERS: Some of you will remember from your history books that our nation’s capitol was built on a swamp along the Potomac River between Maryland and Virginia. Well, we’ve come full circle. Washington DC is now disappearing into a swamp of secrecy where the official view of reality reads like an Arthur Anderson audit.

Take the proposed Department of Homeland Security. A single sentence in the bill for the new department’s creation calls for the Department alone to decide what information the public has a right to know. More ominously, truth-tellers within the department will not be proteced if they blow the whistle on official incompetence or corruption. . .

And here’s the last straw: the department will be exempted from the Freedom of Information Act, meaning everything can be flushed down the memory hole. It’s all part of a pattern, a curtain falling on the public’s right to know.

MOYERS: Eileen Welsome learned just how hard it is to find out what government doesnât want us to know. She won a Pulitzer Prize for searching out secrets dating back fifty years, to the dawn of the atomic age.

EILEEN WELSOME (AUTHOR, THE PLUTONIUM FILES): I had come across a footnote in a scientific report describing 18 humans who had been injected with plutonium during the Manhattan Project.

MOYERS: The Manhattan Project created the first atomic bomb. To study the effects of radiation on human beings, scientists working on the bomb injected unsuspecting Americans with radioactive plutonium. It was all top secret.

WELSOME: The names of the scientists and the names of the patients were blacked out. And I was simply horrified. I wanted to find out who they were, why were they injected, did they develop cancer, did they have pain? What happened to them and why was it done?

MOYERS: She started her search in 1987. But the patients were identified only by number. Welsome wanted their names. So she turned to a law passed by Congress twenty years earlier to safeguard the public’s right to know. Itâs called the Freedom of Information Act…also known as FOIA.

WELSOME: All of these individuals were found with the help of scraps of information that came from the FOIA request that I filed.

MOYERS: She found that, with one exception, none of the patients had any idea what had been done to them. And none of their relatives knew for fifty years.

WELSOME: …If the Freedom of Information Act means anything, it ought to mean that I should get documents on these 18 forgotten people.

MOYERS: Over many years, using the Freedom of Information Act, she forced the Department of Energy to release thousands of documents — a shocking story of half a century of official deceit and dangerous science.

WELSOME: We were able to take these people who had lost their humanity and had been reduced to numbers by the federal government and restore to them their names.

MOYERS: Her reporting brought an official apology from the government and a condemnation of the secret experiments.

JANE KIRTLEY (PROFESSOR OF MEDIA ETHICS & LAW, UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA): Government does make mistakes. And I don’t think the public demands infallibility from its government. I certainly don’t. Accountability is what we demand. And we should have the tools that make it possible for us to compel the government to tell us what it’s up to, how it’s carrying out our business and to instruct the government to take corrective steps when mistakes are made. Ultimately what we’re really talking about is not so much looking back, but looking forward to make sure that the mistakes that have been made in the past are not repeated.

MOYERS: There have been other hard-won battles to open government archives in the almost 40 years since the Freedom of Information Act became law. We have learned about Medicare fraud, CIA assassination manuals, the My Lai massacre. We have learned about underage children forced to work in factories, and how wealthy corporate farms pocket taxpaper subsides.

THOMAS SUSMAN (FREEDOM OF INFORMATION ACT EXPERT): Agencies have never thought it a very good idea to make information public. Surprise! It’s more work. It may, in fact, reveal something that you don’t want known about your decision-making. And it’s always a lot easier to operate in the shadows.

MOYERS: President Richard Nixon knew all about operating in the shadows, as we learned from tapes he recorded in secret.

NIXON tapes:

PRESIDENT NIXON: “We’re up against an enemy, a conspiracy. They’re using any means. We are going to use any means. Is that clear?”

MOYERS: The President of the United States is about to give his aides an extraordinary order. He is instructing them to break into a respected Washington think tank.

NIXON tapes:

PRESIDENT NIXON: “Get it done. I want it done. I want the Brookings Institute’s safe cleaned out and have it cleaned out in a way that it makes somebody else look bad.”

MOYERS: If Richard Nixon had had his way, we might never have heard him ordering that illegal break-in. He claimed the tapes belonged to him and would not be made public.

KUTLER: He made his decision on the 6th to resign and he leaves on the 9th. And there really wasn’t much chance to pack up everything, but things were being packed up and were going to be shipped to California.

And on September 10th, there is an agreement between the Ford Administration the General Services Administration and Nixon for the disposal of this material that would have him allowed him to even to destroy it.

MOYERS: But Congress stepped in with emergency legislation and declared the tapes to be public property. The act would eventually be broadened to set a new standard of openness for the records of all future Presidents.

KUTLER: For twelve years after he leaves office, the President has exclusive access to his papers. In other words, Presidents then are free to peddle their memoirs, use their papers for money. The recent President of the United States has sold his memoirs for $9 million. At the end of twelve years, however, those papers — which were generated with public funds, by public servants, belong to the public.

There was a wonderful consensus that we owe something to our history and to ourselves as a people, to understand what happened. History that’s made up is the endeavor of a totalitarian state — not this state.

MOYERS: Gerald Ford was sworn in as President three minutes after Nixon resigned. Ford swiftly signed the legislation declaring Nixon’s Presidential records public property.

But when Congress — in another reaction to the Nixon scandals — moved to strengthen the Freedom of Information Act, the Ford administration resisted.

MOYERS: The year was 1974. President Ford’s chief of staff at the time was a young man named Donald Rumsfeld. Rumsfeld’s deputy was another young man named Dick Cheney.

THOMAS BLANTON (EXEC. DIRECTOR, NATIONAL SECURITY ARCHIVE): President Ford vetoed the Freedom of Information Act as we know it today. And he vetoed it because he and Rumsfeld and Cheney believed that it took away too much Presidential power. It allowed courts to order the release of documents even when the President said they shouldn’t be released. Then, these guys fought it tooth and nail and lost. Now – these guys are re-opening those battles, and with ninety percent approval ratings, they think they can win.

MOYERS: Back then, Congress overrode Ford’s veto of the Freedom of Information Act.

Today, Dick Cheney is the Vice President of the United States, Donald Rumsfeld, the Secretary of Defense.

KIRTLEY: President Bush, it’s hard to say what his personal views are, but he has included people in his administration who have indicated in the past their predilection towards secrecy and what I would characterize as their outright contempt for the public right to know.

MOYERS: Soon after he took office, George W. Bush made his own feelings known.

QUESTION FROM AUDIENCE (PRESS CONFERENCE TAPE): Would you take this moment to articulate your own view of First Amendment freedoms and give us a sense of the fundamental message that you will send to your Administration as it makes decisions on whether to open or close access to government information?

PRESIDENT BUSH (FROM TAPE): Yeah. I — uh — heh — yes. There needs to be balance when it comes to freedom of information laws. There are some things that when I discuss in the privacy of the Oval Office — or national security matters — that should just not be in the national arena. I’ll give you one area, though, where I’m very cautious and that’s about e-mailing. I used to be an avid e-mailer. And I e-mailed to my daughters or e-mailed to my father. And I don’t want those e-mails to be in the public domain. So I don’t e-mail any more. Out of concern for freedom of information laws, but also concern for my privacy. And, uh, but we’ll cooperate with the press unless we think it’s a matter of national security or something that’s entirely private.

SUSMAN: The President sets the tone for the executive branch. When the President says, “I’ve stopped using e-mail because of the Freedom of Information Act”, you know, I think that that sends the wrong message to those government employees who generate documents on e-mail that constitute official public records. And so to somehow inhibit the generation of records that constitute our nation’s history, is setting the wrong tone.

MOYERS: Once the tone was set, the policy followed. On November 1st of last year, President Bush quietly issued a sweeping Executive Order that — despite its title — effectively repealed the Presidential Records Act. Even some of his strongest supporters were taken aback.

CONGRESSMAN BURTON: We’re talking about things that are not national security issues. We’re talking about other issues that need to be explored and looked at very thoroughly.

MOYERS: Republican Dan Burton had fought to impeach Bill Clinton over White House secrets. Now, it is the President from his own party whose secrecy alarms him.

CONGRESMAN BURTON: The Executive Order very simply says that unless the previous President or the President want those documents from the archives released, they cannot be released unless whoever wants them goes to court to get them.

MOYERS: In other words, if a scholar, historian, teacher, or any citizen wants access to records of previous Presidents, a lawsuit is the only way to get it.

STANLEY KUTLER (PRESIDENTIAL HISTORIAN): And more than that — more than that — it’s wonderful the kind of guarantees that are built in here. If, for example, some obscure history professor somewhere wishes to challenge a former President’s refusal to release his materials and takes him to court, this Executive Order provides that the Department of Justice will defend the former President. You know, Richard Nixon spent a young fortune on lawyers for the better part of twenty years, much of which was spent resisting this kind of thing. Now, Richard Nixon had to pay for that himself, which explains why he wrote so many books to pay for these things. But it’s true. It’s true. Now, here though, President Bush is giving legal cover to his predecessors.

BLANTON: Not only could the former President veto, the former President’s kids, and representatives — and former Vice Presidents. This Executive Order is the first time that Vice Presidents have ever been given their own executive privilege, separate from the President. And I don’t think it’s exactly coincidence that the first Vice President who gets to use this new privilege is George W. Bush’s father, from his tenure under Reagan.

PRESIDENT REAGAN (FROM TAPE): “To eliminate the widespread but mistaken perception that we have been exchanging arms for hostages, I have directed that no further sales of arms of any kind be sent to Iran.”

REPORTER (FROM TAPE): Vice President Bush, did you know about the Contra aid, or not, sir?

MOYERS: Under the Presidential Records Act, tens of thousands of pages from the Reagan administration had been readied for release in January, 2001. That very month, George W. Bush, the son of Reagan’s Vice President, was sworn in as President.

Not only are his own father’s papers now protected by the executive order, he will be able under the order to deny future scrutiny of his own administration.

KUTLER: I knew at the beginning of President Bush’s term that the law was in some trouble because one of his aides said, well, twelve years may not be enough time. And I asked whether what do you need? Fifteen, twenty, twenty-five, a hundred? Or is any too many? And I think that’s it. Any is too many.

KUTLER: And then September 11th happened. An Executive Order that I’m sure had long been in the works came down. And it was justified in the name of national security, and in effect September 11th. And it has nothing to do with September 11th.

MOYERS: It wasn’t only the Presidential Records Act the current Bush administration set out to cripple. In a directive also drafted before September 11th, Attorney General John Aschroft encouraged federal agencies to resist Freedom of Information requests.

BLANTON: On October 12th, Attorney General Ashcroft sent around a memo to all the agencies. And the memo simply said, If you can find any good reason, legal reason — the exact phrase was “sound legal basis” — for withholding information, we’ll back you up.

KIRTLEY: What he’s saying is, the deliberations of the agencies, the information that they obtain and exchange, the whole, how we get to where we are in our governmental policy is not gonna be something that will be readily available to the public. That’s not democracy in my view. It may be an efficient way for a government to operate, but I don’t think we can call it a democracy.

BLANTON: The Ashcroft message is cover your rear, cover our rear. Don’t let information out. And get technical, get legal and damn the torpedoes. We’ll deal with the litigation when it comes.

SUSMAN: Unlike constitutional principles that will survive one Congress after another, one administration after another, the Freedom of Information Act is more fragile. It’s something that I think we all take for granted.

TOM BLANTON: The people’s right to know is on the run right now. We have an administration in Washington that – they see their job in Washington to recoup all the ground that the people’s right to know has gained over the last thirty years. We gained that ground for the people’s right to know in order to prevent another Vietnam or another Watergate or a kind of unaccountable Washington that we used to have.

CONGRESSMAN BURTON (R-IN): I’m a Republican and George W. Bush is one of my heroes. He’s a Republican. I think he’s doing a fine job in the war and the economy. But this flies in the face of openness in government. And while I understand every President wants to protect their turf and keep people from overseeing what they’re doing, it’s the responsibility of Congress to do just that. I believe a veil of secrecy has descended around the administration and I think that’s unseemly.

MOYERS: America is at war and Washington is in a state of high alert. In the name of national security, the white house has denied Congress information it has sought, restricted reporters in their coverage, decreed secret military tribunals, and sealed off thousands of pages of public records.

KIRTLEY: Security and secrecy are not synonymous, but the Bush administration acts as if they are. What’s happening here is that the Bush administration, I feel, is exploiting the public’s legitimate concern about national security and turning that into carte blanche to say, anything we decide we don’t want to share with the public we will withhold on grounds of secrecy.

The irony of all of this is that at the very time when I think the actions of government need to be scrutinized very closely, the roadblocks that have been set up by the Bush administration are going to make it very difficult for the public, for Congress, really for anybody who has an interest in the outcome, which is all of us, to find out what’s going on. And the attitude of the Bush administration, frankly, seems to me to be that it’s none of our business.

MOYERS: But the accountability of power is the public’s business. Just ask Eileen Welsome. Without the Freedom of Information act, what the government did to its own citizens — secretly injecting them with radioactive plutonium — might never have been known. And Elmer Allen might have remained…just a number in a filing cabinet.

WELSOME: I went back to Elmer’s grave and his family had put up a beautiful new headstone. Elmer Allen, the tombstone said, “One of America’s human nuclear guinea pigs.” He had been a human being up until he was injected with plutonium and from that date in 1947 until the day he died, he was a number.

WELSOME: What are reporters gonna be finding out fifty years from now about what is going on right now in the post-September 11th period. I mean are we gonna find out horrendous things in fifty years about what’s been happening in the last four months? And is it going to take fifty years to find out this information?

MOYERS: Since this report first aired, historians and other scholars joined with public interest groups to challenge in court the Bush Executive Order limiting access to Presidential records.

Their pressure has led to release of thousands of pages of documents while the suit is now pending before a federal judge. Vice President Cheney, meanwhile, continues to lead the fight to keep Americans from knowing what their government knew about terrorist threats before September 11 including those two messages the National Security Agency intercepted on the eve of 9/11 but didn’t translate until after the attacks.

The government’s obsession with secrecy is all the more disturbing because we are fighting a war without limits — without a visible enemy and no decisive encounters. We don’t know what’s going on, how much it’s costing, where it’s being fought, and whether it’s effective. That gives a handful of people enormous power to keep us in the dark. And it justifies other abuses.

Vice President Cheney still resists our knowing how corporations were allowed to decide the Bush energy policies that handed them billions of dollars in taxpayer subsidies. This is potentially a bigger scandal than the heist of Teapot Dome that rocked the Harding Administration. That one too involved vast amounts of oil. Look it up on pbs.org. It’s no secret.

It’s no secret. That’s it for “NOW” I’m Bill Moyers.