Try this thought experiment. Pretend that it’s the spring of 1970. President Richard Nixon has just sent US troops into Cambodia. He thereby expands the Vietnam War, a costly undertaking already ongoing for years with no sign of victory in sight.

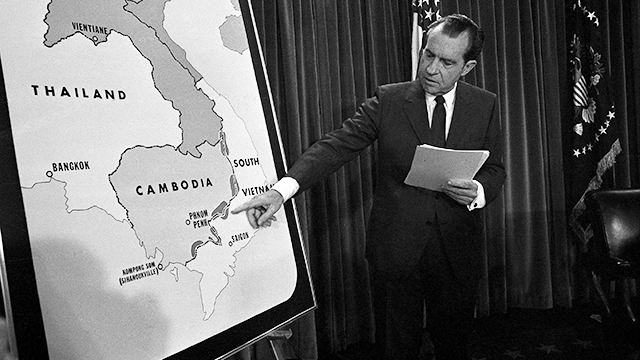

US President Richard Nixon poses in the White House after his announcement to the nation April 30, 1970 that American ground troops have attacked, at his order, a Communist complex in Cambodia. Nixon points to area of Vietnam and Cambodia in which the action is taking place. (AP Photo)

Now imagine further that Nixon sends a message to Congress asking that it authorize him to do what he has already done (while simultaneously insisting that even without legislative approval he already has the necessary authority).

This essentially describes the present-day position of the Obama administration, requesting ex post facto congressional approval of the military campaign against the Islamic State that it launched several months ago.

Now, let’s take the thought experiment one step further. Imagine that Congress takes up Nixon’s request and debates whether or not to give its consent to what he has already done. What would be the tenor of that debate? Would members of Congress confine their inquiry to the specific question Nixon had posed: Whether or not to okay the Cambodian invasion? Or would the Cambodian issue open the door to a more searching examination of the premises and conduct of the Vietnam War and indeed of the Cold War itself?

We can’t know, of course, but it seems likely that members of Congress would have seized the opportunity to look beyond the matter immediately at hand. In all likelihood, a debate over whether or not to give Nixon the go-ahead in Cambodia would have become a debate about the several decades of policy decisions that had culminated in the Cambodian invasion.

In Oct. 20, 2014, thick smoke and flames from an airstrike by the US-led coalition rise in Kobani, Syria, as seen from a hilltop on the outskirts of Suruc, at the Turkey-Syria border. The airstrike is part of the ‘Operation Inherent Resolve’ by the US government to diminish the jihadist group ISIS. (AP Photo/Lefteris Pitarakis, File)

Back in 1970, when the predicament was the Vietnam War, those questions demanded urgent attention. Today, the enterprise once known as the Global War on Terrorism, now informally referred to as the Long War or the Forever War or (my personal preference) America’s War for the Greater Middle East, defines our predicament. But the questions remain the same as they were when Cambodia rather than the Islamic State represented the issue of the moment.

So President Obama’s requested Authorization for the Use of Military Force (AUMF) could not have come at a more propitious moment. The proposed AUMF presents the Congress with an extraordinary opportunity — not to rubber stamp actions already taken, but to take stock of an undertaking that already exceeds the Vietnam War in length while showing not the slightest sign of ending in success.

The people await the appearance of political leaders who can summon up the courage to acknowledge that failure and to initiate the long overdue discussion of how to chart a different course.