This post first appeared at ThinkProgress.

People living close to natural gas wells in southwestern Pennsylvania are more than twice as likely to report respiratory illnesses and skin problems than those living farther away, according to a new study from Yale University.

Dr. Peter Rabinowitz, a former Yale School of Medicine professor who now teaches at the University of Washington’s School of Public Health, got the results by randomly surveying 180 households with 492 people in Washington County, Pennsylvania. Washington County is in the heart of the Marcellus Shale, one of America’s fracking hotspots — and arguably the epicenter of fracking-related pollution complaints and industrial accidents.

Of those surveyed, Rabinowitz found that 39 percent of people living less than 0.6 miles from a gas well reported upper-respiratory problems like sinus infections and nosebleeds, compared to just 18 percent of people living more than 1.2 miles away. For skin problems like rashes, 13 percent living close to the wells reported irritation, compared to only 3 percent living further away who said the same.

Rabinowitz said that his findings represent “the largest study to date of general health status of people living near natural gas wells.”

The study, published in the peer-reviewed journal Environmental Health Perspectives, is careful not to claim outright that the fracking itself is causing the health problems. Rather, it solely states that there are higher rates of illness in households closer to gas wells. To say that drilling or fracking causes illness would require more research, Rabinowitz said.

“It’s more of an association than a causation,” Rabinowitz told the New Haven Register. “We want to make sure people know it’s a preliminary study… To me it strongly indicates the need to further investigate the situation and not ignore it.”

Rabinowitz is not the first to assert that more research needs to be done into the health impacts of fracking.

Just last week, scientists at the University of Texas published research stating that 30 percent of water wells near Texas fracking sites contained higher-than-normal levels of arsenic. However, the researchers stated that their findings were not conclusive in stating that the contamination is because of fracking.

“We think that the strongest argument we can say is that this needs more research,” Brian Fontenot, the paper’s lead author, said at the time.

In addition, preliminary scientific research is finding more and more of a connection between birth defects and the proximity of the child’s mother to a natural gas well. Still, scientists generally agree that more research needs to be done before a conclusive statement can be made about whether that proximity to natural gas drilling actually causes birth defects or other health problems in babies and mothers.

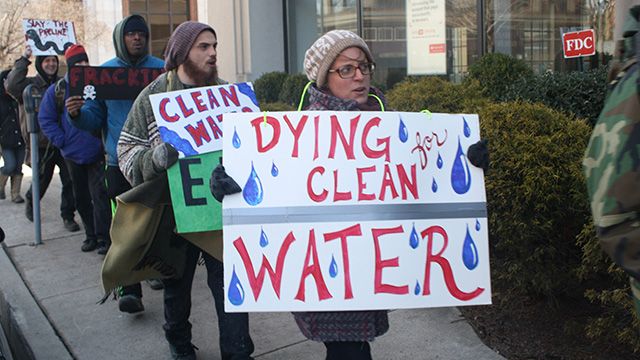

Fracking is a controversial yet popular technique used to stimulate natural gas wells underground by injecting high-pressure water, sand, and chemicals miles-deep into subsurface rock, effectively cracking or “fracturing” it, making the gas easier to extract. It has been controversial in part because of how quickly the practice has spread in the United States, without much credible scientific information regarding the potential impact on public health.

Pennsylvania has had more than 6,000 hydraulic fracturing wells drilled within the last six years and zero state studies on their health impacts. Because of the lack of research, it’s been increasingly hard to prove that families can be sickened by drilling.

Natural gas drilling in Pennsylvania has skyrocketed under Gov. Tom Corbett. He has expanded fracking in Pennsylvania’s state parks and forests, and in 2012 implemented a controversial state oil and gas law, known as Act 13, which severely restricts the ability of local governments to have control over drilling in their area. Multiple portions of the law have since been ruled unconstitutional by the state Supreme Court.