In the US, most of the analysis of what’s happening in Iraq comes to us from Americans. A handful of our “Iraq experts” know the country intimately; others have traveled through it embedded with US troops or experienced it from the alternate universe of the heavily fortified US Green Zone during the height of the occupation. But a majority of the people whose supposed insights shape our views of Iraq never set foot there.

For an Iraqi perspective on what’s going on — and for some context — we turned to Raed Jarrar. Jarrar was born and raised in Baghdad. He lived there on and off under Saddam Hussein’s rule, and he experienced America’s “Shock and Awe” campaign from the receiving end.

After the invasion, Jarrar founded an NGO that did reconstruction work in Iraq. He worked as the country director for the first door-to-door survey of Iraqi civilian casualties conducted after the invasion.

When the situation in Baghdad became unbearable, Jarrar emigrated to the US and became a writer and peace activist. He translated the controversial Iraq Oil Law proposed by the Bush administration in 2007, and has consulted with several international humanitarian groups.

A transcript of our discussion is below; it’s been edited for length and clarity.

Joshua Holland: Can we draw a line from the Bush administration’s decision to completely dismantle the Iraqi government of Saddam Hussein – including its security apparatus – to the chaos we see now?

Raed Jarrar: We can, but I think you need to begin earlier than that. The US intervention in Iraq officially started in 1991. And in some ways it has not stopped yet.

This included a couple of wars, 13 years of really harsh economic sanctions, and as we all know, eight years of military occupation followed by a continuous intervention in Iraq’s domestic politics. Contrary to what many people here think, while the US ended its military occupation at the end of 2011, it never stopped interfering in Iraq’s business. The US continues to sell the Iraqi government billions of dollars worth of weapons, we have training programs for Iraqis, and of course we’re picking and choosing who to train and who to arm in a situation that’s extremely complicated.

Holland: How do you respond to Americans who say, “Well, Sunni and Shia, they hate each other — it’s an ancient blood hatred and we have nothing to do with that. It’s not our fault that they’re at one another’s throats.”

Jarrar: You can say this about many other sects and religions whether they are Christian or Muslim or whatever. But there is a political dimension to these historical differences.

Obviously, there are theological differences as well as political and social differences. But the fact is that Iraqi Sunnis and Shiites managed to live in the same country for a long time without killing each other, and they lived in the same neighborhoods. They intermarried — I am half Sunni and half Shiite. I am one of many Iraqis who was born into these mixed marriages.

That was before the US intervention. The US destroyed that Iraqi national identity and replaced it with sectarian and ethnic identities after 2003. I don’t think this is something that many Iraqis argue about, because you can trace the beginning of this sectarian strife that is destroying the country, and it clearly began with the US invasion and occupation.

That’s not to say that Iraqis don’t have agency over their own country and lives – they could and should have worked on bridging the gaps. But it’s not easy to fix these huge political and religious differences when the situation is as complicated as Iraq — and when the US is funding and training one side of this conflict with tens of billions of dollars, it’s not easy to reach a point of national healing, where Iraqis work together and live in peace.

Holland: A few years back, Nir Rosen wrote that an “obsession with sects informed the US approach to Iraq from day one of the occupation.” But how did this sectarian animosity emerge at the neighborhood level? Take me into a mixed neighborhood and tell me how the invasion caused people who used to be neighbors to turn against each other.

Jarrar: It started just by bringing up people’s sectarian divisions. I think making it a political identity was the first destructive force. And this happened right after the fall of Baghdad, when the US created the Iraqi Governing Council. The IGC was the first entity in Iraq’s contemporary history where people were selected based on their sectarian and ethnic identity. It had never before been the case that people were selected to serve because they were Sunni or Shiite or Kurdish. That brought it up to the surface. They started this quota system for political affiliations and then the ruling parties started playing on these divisions.

So before people started seeing the changes in their neighborhood, they started seeing changes in the political rhetoric and in the news coverage and in the way that they perceived themselves.

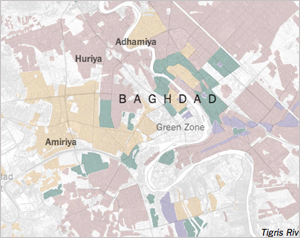

2009 map showing how religious sects were segregated in Baghdad neighborhoods after the war. See more maps and the full feature at The New York Times website.

Now fast forward a few years. There’s not enough security. And Iraq witnessed one of the largest ethnic and sectarian cleansing campaigns in the region’s history. The number of Iraqis who were displaced either inside or outside of the country was around 5 million. That’s out of a population of less than 30 million. So one-sixth of the population were forced to move out of their homes. This is like having 50 million Americans pushed out of their homes within a few years. It’s a crazy number.

The Baghdad neighborhood where I used to live before I emigrated to the US, it became a Sunni neighborhood. All the Shiites were targeted — they were killed, or they moved to another neighborhood. And the neighborhood that I lived in before that one became a Shiite neighborhood, because all the Sunnis were targeted and moved out.

There was this very sophisticated system of neighborhood-to-neighborhood cleansing in Baghdad. And there was a deliberate effort to not attack Sunnis in Sunni neighborhoods, just to keep them there — the same with Shiites in Shiite neighborhoods.

Then the larger picture is that there were entire cities that were completely cleansed of one ethnicity or the other. In a few cities in the south, they kicked out all Sunnis; a few cities in the north kicked out all Arabs or all Kurds.

Many people accuse the militias affiliated with the ruling parties that were supported by and funded by the US of being involved with this program of cleansing.

And it created a new reality. I used to say Iraq will never be separated or partitioned, because of the demographic realities. There were millions of Shiites who lived in what the US wanted to have as a Sunni partition, and vice versa. [Ed note: In 2007, the US Senate passed a nonbinding resolution supporting “regional federalism” in Iraq that would have divided the country into three semi-autonomous regions along ethnic and sectarian lines.] Now that’s completely changed. Today, the new demographic reality has opened the door for sectarian war, it has opened the door wide for partitioning and for what has been going on this week.

So the deterioration we see today didn’t happen in a few months. It happened over a long, long period of time. There was so much destruction and death and displacement and ethnic cleansing imposed upon Iraqis before we reached this week of actual sectarian civil war.

Holland: You lived under Saddam Hussein, and you lived under the first years of the US occupation. There is an argument, especially from conservatives, that life under Saddam Hussein was so heinous that even with what followed – with the many missteps of the occupation — we were ultimately justified in going in to depose this monster. What’s your reaction to that?

Jarrar: First let me say that this argument is fairly new to the history of this conflict. Earlier, the proponents of intervention in Iraq did not use Saddam Hussein and his atrocities as standards for what the US would bring to the country. They promised some utopian ideals of happiness and democracy and equality for all. So the mere fact that they are trying to defend their crimes by comparing them to someone else’s crimes is actually evidence of their failure.

In the 1990s these things started falling apart — after the 1991 war. We saw partitioning of the north of Iraq to what became Iraqi Kurdistan. People became a little bit more religious, and under the sanctions [that the UN Security Council imposed between the two Gulf Wars] there was more corruption. But it continued to function better than it did after the occupation even under the sanctions, which is amazing when you think about it.

Iraq was exporting an average of $100 billion worth of oil every year. That’s actually more than the budgets of Jordan and Syria and Lebanon and Egypt combined. And under the occupation – and after it – the government failed to provide its citizens with electricity, with water! With a decent road that they could drive on. The most basic services are not provided. Iraq has been among the most corrupt countries in the world for the last twelve or thirteen years, according to Transparency International.

So the short answer to your question is that before 2003, Iraq was not a very happy place to live, but it was home for millions of people. They went to work, and they had their basic needs satisfied. They could not express themselves politically. But after 2003, people still could not – and cannot – express themselves politically and they also lost all of the security that they used to have and all of the basic services.

So I don’t think many Iraqis actually would disagree that the US occupation and invasion and everything that happened after it made the country much worse.