One of our millennial colleagues, Panyin Conduah, asks:

“Who decides how the presidential debates are staged? And why aren’t Gary Johnson and Jill Stein allowed in?”

Short answer: The tradition of holding presidential debates is as old as…well, the baby boomers. Though debate organizers like to portray themselves as part of a grand tradition dating back to the fabled 1858 series between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas (who actually were running for the Senate at the time), it wasn’t until the television era that unscripted, face-to-face encounters of presidential contenders became a regular part of the political landscape.

And it wasn’t until 1976, when the nonpartisan League of Women Voters stepped in, that it became a regular quadrennial affair. The League continued in its role as debate sponsor until the mid-1980s, when the two major political parties big-footed them out of it. Today there are new efforts underway to modernize and democratize the debates. Some of them will affect the format of Sunday’s “town hall,” featuring Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton and her Republican rival, Donald Trump — read on.

The origins of modern-day presidential debates

The famed 1960 debates between then-Sen. John F. Kennedy (D-MA) and Vice President Richard M. Nixon heralded the impendiing power of television over politics and were widely believed to have helped Kennedy win the White House in that year’s election squeaker. Perhaps because of that, it would be 16 years before the nation would be treated to another such series.

But the successful efforts that year by the League of Women Voters to organize debates between Republican President Gerald Ford and his Democratic challenger Jimmy Carter — as well as a debate for their running mates, Republican Senator Bob Dole and his Democratic Senate colleague, Walter Mondale — established a new tradition. “The League of Women voters institutionalized presidential debates,” former League president Dorothy Ridings said in a video history prepared by the organization.

For the next three election cycles, the League served as the organizer and moderator of the presidential debates. The task was often thankless, as it involved cajoling candidates to the table and catering to many of their demands. As vividly described by Harvard historian Jill Lepore in a recent New Yorker article and by former Federal Communications Commission Chairman Newt Minow in his 2008 book Inside the Presidential Debates, there were fights over formats and moderators and worries about whether the candidates even would show up. In 1980, for instance, then-President Carter refused to share a stage with Republican Ronald Reagan and third-party candidate John Anderson in a debate that was moderated by Bill Moyers (though Carter did later take on Reagan mano-a-mano). After the 1984 cycle, the political parties began to muscle their way into the debate-organizing process. The party chiefs argued that their imprimatur would guarantee candidate participation. But the League pushed back. In a history of its involvement in the presidential debate-organizing business, the League of Women Voters Education Fund explains why:

The LWVEF argued that a change in sponsorship that put control of the debate format in the hands of the two dominant parties would deprive voters of one of the only chances they have to see the candidates outside of their controlled campaign environment.

For a while, the two groups worked in uneasy coexistence. But in 1988, one year after the two parties established the Commission on Presidential Debates, the League angrily refused to sponsor a debate between Democratic nominee Michael Dukakis and Vice President George H.W. Bush because it did not approve of the arrangements the candidates made “behind closed doors” regarding the format and rules of engagement. “Never in the history of the League of Women Voters have two candidates’ organizations come to us with such stringent, unyielding and self-serving demands,” the League’s president, Nancy Neuman, said in a statement at the time. “The League has no intention of becoming an accessory to the hoodwinking of the American public.”

The era of presidential debates organized by the two major political parties was born.

So what’s the Commission on Presidential Debates?

As Minow, , a key player in getting the modern presidential debates off the ground, recounts in his book, the commission was organized as a nonprofit corporation with the encouragement of civic leaders interested in keeping the debates going and with seed money from the Twentieth Century Fund. It exists only to organize the fall presidential debates every four years and has nothing to do with the proliferation of free-for-alls that have come to characterize debates among presidential primary candidates. Those are organized largely by political organizations and cable TV networks.

Though the Commission is nominally nonpartisan, the involvement of the two major political parties is obvious: The first co-chairs were Frank Fahrenkopf, former head of the Republican National Committee, and Paul Kirk, former head of the Democratic National Committee. Kirk, a close friend of the Kennedy family, resigned to serve out the term of Sen. Edward Kennedy after the Massachusetts Democrat died. His replacement: Mike McCurry, a longtime Democratic operative best known as former President Bill Clinton’s press secretary. The current board of directors is comprised of political and network stalwarts, civic leaders and academics, most of them members in good standing of the Washington establishment.

Heading into the 2012 presidential debate season, the Commission reported receiving more than $7 million in contributions. Like all 501(c)3 organizations, it is not required to list the sources of its funding, but at this year’s first presidential debate, co-chair McCurry thanked a number of corporate, foundation and civic sponsors, noting that the foundation gets no money from either of the political parties and that it’s “totally nonpartisan.”

Not everyone agrees with that assessment.

Commission critics and the knotty question of who gets invited

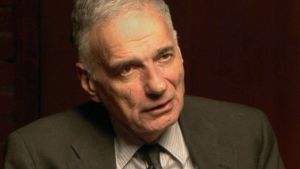

Detractors run the political gamut. On the left, Ralph Nader, a frequent third-party candidate who has never made it to the debate stage, dismissed the presidential debates in an interview with BillMoyers.com as a “political corporate duopoly” designed to keep disruptive new ideas and political figures from surfacing. On the other side of the political spectrum, Steve Forbes uses uncannily similar language.

This year, the conservative National Review has called to “End the Debate Cartel,” and on the left, Think Progress has raised doubts about the arrangements too.

Both publications have questions about the inability of political outsiders to get a place in one of the most important forums of the campaign. That remains the knottiest problem facing debate organizers. On the one hand, allowing everyone who is running for president to take the stage would guarantee that no one gets heard. Nearly 1,900 individuals notified the Federal Election Commission of their intention to run for president in 2016. So how to decide who makes the cut?

The Commission’s eligibility criteria say that to make the debate stage, a candidate must be on the ballot in enough states to get 270 Electoral College votes — the number required to win the White House — and register at least 15-percent support in five major national polls. In 1992, Ross Perot qualified. But four years later, he was excluded from the debates, a decision that disappointed The New York Times. Perot’s attempt to sue his way onstage won bipartisan support, but he, like current Green Party candidate Jill Stein and the Libertarian Party’s Gary Johnson, was unsuccessful.

This year, neither Stein nor Johnson have reached the 15-percent threshold in national polls. But with more and more voters expressing discontent with the political status quo — nearly one-third now identify as independent and this year’s presidential nominating contests dramatically demonstrated the electorate’s strong aversion to the party establishments — it seems likely that future debates could may be challenged by candidates from outside the two-party system who have strong claims to a place on the stage.

That, and a general sense that the debate format is in need of an overhaul has led to a number of groups recommending changes.

Ideas for improving debates

Minow’s recommendations, made in his 2008 book, were echoed last year by a working group the Annenberg Public Policy Center commissioned to write a report on “Democratizing the Debates.” Among the ideas floated in their report: radically changing debate formats to get away from the canned speeches and rehearsed “gotcha” quotes; making the selection process for moderators more transparent — or eliminating them altogether; changing the debate schedule (to account for early voting) and making them more accessible to candidates and viewers.

Meanwhile, as Minow was publishing his book, a group of tech innovators joined forces to battle the TV networks’ copyright on debate footage. The group, which was ultimately successful in its efforts to liberate the footage for public use, has morphed into a nonprofit called OpenDebateCoalition with a new mission: Creating “crowdsourced” political debates in which the questions come from the voters. This year, the wildly disparate group (members range from the Young Republicans to the Sierra Club) already has helped organize a US Senate debate in Florida and a congressional debate in Massachusetts.

The group hopes to get its foot into the presidential debate door this weekend. Opendebates has set up a website at which questions for Sunday’s debate can be submitted and voted up or down. Voting will continue right up to air time, says OpenDebates spokeswoman Lilia Dixon, who adds that the debate moderators, CNN’s Anderson Cooper and ABC’s Martha Raddatz, have agreed to try to incorporate some of the group’s questions into the town hall format. Possibly feeling some heat, the Commission itself has announced a series of initiatives to incorporate social media into the debate process.

Based on his own long experience, Minow writes that any debate format is bound to be “imperfect.” But the good news for voters is that there’s no debate about the value of political debate. And there’s no dearth of ideas about how to make them better.