Bill Moyers sits down with Supreme Court Justice Harry Blackmun to discuss, the Constitution, his term on the bench and how Blackmun’s landmark decisions held no ideological pattern.

WATCH A CLIP

TRANSCRIPT

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Sometimes, I think we — we could scream at the cases that come to us, but it just bears out the old de Tocqueville admonition of years ago that, eventually, every social question then is made into the legal one, and comes before this Court.

BILL MOYERS: It is two hundred year old.

MALE VOICE: One country, one constitution, one destiny.

BILL MOYERS: We have revered and debated it.

MALE VOICE: Like the Bible, it ought to be read again and again.

MALE VOICE: People made the Constitution and the people can unmake

BILL MOYERS: We have honored and criticized it.

FEMALE VOICE: My faith in the constitution is whole. It is complete.

MALE VOICE: The prejudices of the day are called constitutional law.

BILL MOYERS: We even fought a bloody civil war over it.

MALE VOICE: This covenant with death, this agreement with hell, this refuge of lies.

BILL MOYERS: But we have lived with it. We are still living with it today, still debating it, still In Search of the constitution.

BILL MOYERS: I’m Bill Moyers. What does this have to do with the Supreme Court? Well three times, in the past fifty years, major league baseball players appealed to this august body to give players the right to move from team to team; to unshackle them from the servitude of the reserve system. The last time, Supreme Court Justice Harry Blackmun passed the ball to Congress, on the grounds that previous decisions gave baseball an exemption from the anti-trust laws, and Congress had never acted to remove that exemption. Congress was up to bat, according to Justice Blackmun, but chose to sit on the bench. We’ll spend this hour with Justice Blackmun, talking about how the Supreme Court reaches into just about every aspect of our lives, from how Americans play to how they pray. justices of this Court are the ultimate umpires of our Constitution. But wearing those black robes are real human beings who anguish over their decisions. When they make a call the crowd doesn’t like — well, just ask Harry Blackmun what it’s like, there behind home plate.

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Being on the federal bench is no place to win a popularity contest. One … one never can do that … And I suppose, that is one reason that the Founding Fathers made … federal bench … appointments…the popular phrase is “for life”; that isn’t true; it’s the Constitution says for good during good behavior. And our daughters always remind me of that.

BILL MOYERS: Harry Blackmun had been legal counsel to the famed Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, and, then, a judge on the Circuit Court of Appeals when Richard Nixon appointed him to the Supreme Court in 1970. His appointment to the Court was confirmed unanimously, and it was widely thought the new justice would strengthen the conservative wing of the Court, reading the Constitution strictly. But, within three years, justice Blackmun spoke for the Supreme Court majority in one of the Court’s most liberal, historic and controversial decisions of the century: Roe versus Wade — granting women constitutional protection for abortion.

This from his opinion: “the Constitution does not explicitly mention any right of privacy. In a long line of decisions, however, the Court has recognized that a right of personal privacy, or a guarantee of certain areas or zones of privacy, does exist under the Constitution.”

Justice Blackmun’s decisions hold to no ideological pattern. In cases concerning the relationship of the states and federal government, he has counseled restraint by the Court. He advocated a libertarian position, concerning free speech in advertising: No government interference whatsoever.

But, on decisions regarding anti-trust and securities law, he championed vigorous government regulation. And he has broadened the Court’s basic ideal, equality before the law, to aliens in America. Blackmun, the man of the middle, refuses to wear a label.

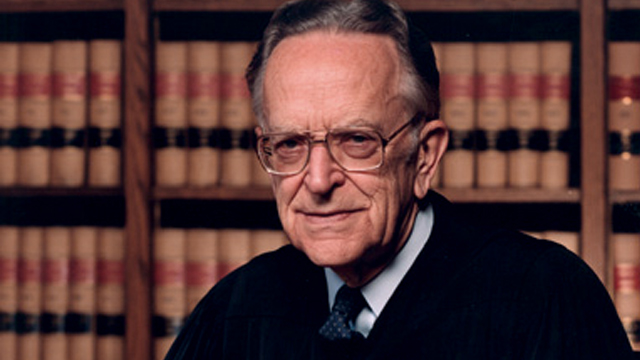

Justice Harry Blackmun (Wikicommons)

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Of course, some people felt … when I came here in 1970 … that I was bound to be a … a conservative, if not an ultra-conservative.

BILL MOYERS: A strict constructionist , they said.

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: And I … I can see it … till, today, repeated … An unknown conservative judge from the upper Midwest. And people often ask me … why have I changed: I give two answers, and one is that the old Felix Frankfurter comment that … “I haven’t changed: it’s the court that’s changed under me.” Frankfurter of course came here, supposedly, to be an avowed liberal, and turned out to be a fairly conservative person. The other reason is I like to think that one grows, constitutionally, here. And … is forced to take positions on Constitutional issues…that he was not forced to positions or even think about before… And, of course, what … what happens, so often, is the media, particularly the printed press, like to set us up in…in certain pigeon-holes.

BILL MOYERS: Uh-huh.

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: And, every now and then, the round peg doesn’t fit into the square hole.

BILL MOYERS: Liberal or conservative?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Yea.

BILL MOYERS: Or judicial activist or judicial conservative?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Exactly. Now, I hope I’m fair in saying this, that … well, it’s easy to say that … well, it’s easy to say that … Justice Brennan and Justice Marshall are … on the liberal side of the Court, and the Chief Justice and Justice O’Connor and … now, Justice Scalia … are on the conservative side. And the rest of us, I hope, are in the center.

This isn’t true for … in my view, anyway, for every case … Some of us are more conservative in certain areas, and more liberal in certain other areas.

BILL MOYERS: When it was said, so often, that you were a strict constructionist, and that’s why President Nixon appointed … did you know what they meant by strict constructionist?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Not exactly, and I still don’t … know. Well, I … I know the general definitions that one uses for it, but…

BILL MOYERS: What’s your definition?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Hmm … You challenge me, and I’m not sure I can give you an answer … because I … I don’t like the phrase very well. I … I hope that all of us here are … just good judges … And…

BILL MOYERS: Trying to do?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Call the shots as he sees them; he or she sees them. I have seen very little political voting in the seventeen years that I have been here. I… I think there’s honest voting; honest convictions. Oh, once in a while, I wonder, a little bit, but … the judges with whom I’ve served have been trying to do the very best they can on these very difficult issues.

This is not to say that we don’t have built-in biases. We have different experiences; different backgrounds. Some Of us come from affluent families… some of us come from just the opposite. The former Chief Justice and I grew up in a… very lower middle-class neighborhood in St. Paul, Minnesota. We didn’t have anything. And … I’m not… I’m not sure we were aware of it… we enjoyed our childhood and… got along all right.

But I think, those things tend to make one what he is in later life, to a degree.

MOYERS: I look at your record. I would say that you practice the … judicial philosophy of just desserts. In fact, someone once wrote, “Justice Blackmun insists upon results that accord with his view of the real world.” And that seems, to me, to rescue your record from a strict embrace of ideology…to a pursuit of the meaning of the Constitution in a particular case, at a particular time.

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: I’m not so sure that I have a judicial, constitutional ideology, at all. To me, every case involves people. I like to keep people in mind, and how it affects their lives, and… what they have done, what our decision is going to do with them, and with their fortunes. I think, if we forget the humanity of the litigants before us that we’re in trouble … No matter how great our supposed legal philosophy can be.

BILL MOYERS: Do you try, with your mind’s eye, to see the individual behind that caser beyond .the lawyer who’s making the argument in front of the bench?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: I try, and, often times, they’re in the Court, in the final arguments, here, and I … if I can spot that, I like, at least, to look at him or her.

BILL MOYERS: It does… I … it does seem to me that you are always struggling to put yourself, in the other person’s show whereas, an ideologue is always trying to put his shoes on someone else’s foot, whether they fit … or not.

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: That’s a good way to put it.

BILL MOYERS: Tell me something about your workday. I don’t think most people, out there, have any idea what a Supreme Court justice actually does from morning until evening.

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: I’m down here at 7:30 in the morning. And … I have breakfast with the clerks, every day … at about five minutes after eight And I’m with them, in the cafeteria, downstairs, until nine o’clock. This is the one-hour of the day that I can have with my clerks, uninterrupted.

BILL MOYERS: You discuss cases and … go over the routine of the day, the issues that are coming up?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: We discuss yesterday’s arguments, and tomorrow’s arguments, and the briefs, and, sometimes, we talk of baseball or…

BILL MOYERS: And, then, you work all day, hearing arguments; reading?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: And … well, if we’re in session, of course, we’re on the … the bench four hours a day … from ten to twelve, and one to three … One would say those are bankers’ hours. But … four hours of listening to lawyers, in one day, is enough. And I say that not critically. I think, there comes a point where one’s powers of absorption begin to dry up a little bit.

I leave at seven o’clock … Have dinner with Mrs. Blackmun, Dotty, for an hour, and then, I work, usually, ’til midnight. Now, I’m sure, some of the others don’t put in hours like that, but maybe I’m the dumbest of the lot, and it just takes me that long to do it in the way that I want to do it.

BILL MOYERS: Do you take the weekends off?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Well, I like to get away … as a matter of fact, I think I have to get away from Washington and this building, once in a while, just to … (LAUGHS) … maintain my sanity.

This is a very … close … intimate association that the nine of us have. We … we’re working constantly with each other under … conditions of … a certain amount of agreement, and a very definite amount of disagreement. And … I think there’s … it’s easy to become isolated in an ivory tower, in this building. But this isn’t, for me, much of a fun job. I think it is for some. I think, Hugo Black, for instance, found it exhilarating; he liked it; it was fun. I think it’s hard … hard work, the hardest job I’ve ever … I’ve ever had. But it is a fantastic experience that no lawyer would turn down. So, I … I’m glad I’ve had the opportunity. It’s been a privilege to serve this long on this Court.

BILL MOYERS: Do justices ever think of quitting when they’re ahead? (LAUGHS)

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: No. (LAUGHS) And … if I had any sense, I’d quit, you see, at this age.

BILL MOYERS: At one time, you said you would think about it when you turned … 75? Now, you’re 80.

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: No. Hold it. Give me a little more time.

BILL MOYERS: How old are you?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: … I’m 78, now.

BILL MOYERS: 78. But you didn’t when you were 75. Do you ever think about it?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: All the time. Uh-huh.

BILL MOYERS: … But you don’t.

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Not as of now, no.

BILL MOYERS: Uh-huh.

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: … But I have some spies … spotted here and there; a number of them at Mayo’s. I used to be at Mayo’s … on their staff, and … and I think they’ll … be honest enough to let me know when the signs of senility are greater than they are now.

BILL MOYERS: That is a question that’s often intrigued me. What happens if a justice, who’s … whose vigor of mind and health is so important to the laws of this nation, were to suffer the approaching indications of senility … does he have safeguards? Does he make sure that there are vigilant … vigilant friends giving him the best advice?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: I suspect they don’t. And, of course, there are one or two … instances in history where this has been very difficult … the most notable example is … Oliver Wendell Holmes, Junior… who was asked to step down.

BILL MOYERS: By his peers?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Uh-huh.

BILL MOYERS: Because he was?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Ninety-two, and … sleeping in the Courtroom, and … had reached the point … and to his … great credit, he did it immediately … But when one’s at this age, I think he… he watches fairly carefully. Or ought to. And there are four of us that … there were five, until the old Chief retired … four of them older than I … And I reminded my older brethren, every once in a while, that I was the youngest of the five. (MOYERS LAUGHS)

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: And it just burned them up, you know.

(LAUGHTER)

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: They weren’t very much older, but they were a little bit older.

BILL MOYERS: What is the most important thing you would want me to understand about the Supreme Court? What would you say to me to try to explain what the Court’s role in my life is?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: One thing that the public often does not appreciate is that much of what we do, up here, is done … comes out by way of compromise. There are nine of us. And … many times, the … prevailing opinion … it might be five to four, or six to three, or even seven to two … sometimes, there are paragraphs or sentences or statements in the prevailing opinion that the primary author would prefer not to have there. But, in order to get five votes together … we have to get something that those five can agree to. We try to accommodate everyone that we can. But, sometimes … a judgment here is by a vote of five.

BILL MOYERS: One vote.

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: One vote.

BILL MOYERS: Can people have confidence in a process that depends so much on … on personal persuasion and brokering as opposed to just the sheer force of the law itself; the intuitive sense of justice?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: If we all agreed … there wouldn’t be any point in having nine of us; we might as well have the Chief Justice, whoever it is, and … and let it go at that; have one person. But we’re there, we’re all from different backgrounds; most of us, different experiences, different types of education. And different attitudes, and … about … the American government and the political process.

BILL MOYERS: Sometimes, one goes on with an opinion … goes along with an opinion, not quite certain that it’s … it’s right, but that it’s necessary, at the moment, on the basis of that argument; that evidence. And, then, later, something happens to change one’s … mind.

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Exactly. The facts may be different … It may bring out some … overtones or features that one hadn’t thought before … about before, or that counsel hadn’t brought to our attention. There was one, a couple of years ago, in which … I wrote a concurrence saying that … I’m uneasy about it; this is the way I feel now, but, maybe, in the next case, I’ll feel otherwise. That’s the exciting thing, I feel, about the law, is that it is … not a rigid … animal, or a rigid … profession. It’s a constant search for truth … as we define it, however we define it.

BILL MOYERS: But you do define it.

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Have to. Sure … we define it by making decisions. I suppose.

BILL MOYERS: But it is … the truth, not THE truth. Because … if one of you changes your mind …

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: You express it well, with your emphasis, as you ask the question … Between THE truth and the truth. (BASEBALL CROWD NOISE)

BILL MOYERS: Even baseball players come to the Supreme Court for the truth of the moment.

BILL MOYERS: In 1970, center-fielder Curt Flood, of the St. Louis Cardinals, refused to report to Philadelphia after being traded by his management. The reserve clause bound players to their original owners, who could sell or trade them without consultation.

CURT FLOOD: It’s been a master-and-slave relationship. As long as … as long as you do what I say to do, you’re fine. That’s great. (CROWD)

BILL MOYERS: In 1922, the Supreme Court had ruled that baseball was not subject to the anti-trust laws. But Flood filed suit to free himself from what he thought was an arbitrary and unfair contract. (CROWD NOISE UNDER; THEN FADE)

BILL MOYERS: But you quoted Grantland Rice on “Casey at the Bat” Millions never heard of Keats, Shelley, Burns and Poe; but they knew the air was broken by the force of Casey’s blow.”

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Exactly. (LAUGHTER) Exactly.

BILL MOYERS: You don’t get to write many lyrical opinions, like that, do you?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: No, and I … When I’m asked, I say that I … had more enjoyment out of writing that opinion than any other … case I’ve ever had. I was pleased … when that one came to me. And, of course, I … I indulged in that sentimental journey in Part One of it … with the … history of baseball; that … it had two results, which have amused me. The first was, the … complete antagonism of the sports writers … in Washington and New York. (MOYERS LAUGHS) I think they felt I had … impinged on their turf … And the other was the fact that two members of the Court didn’t join it; they joined the rest of the opinion, but not the sentimental journey.

BILL MOYERS: Why?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: They never told me, but, I suspect, because they felt that it was … beneath the dignity of the Court. (MOYERS LAUGHS)

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: I … I would do it over again, because I think it was … baseball deserved it.

BILL MOYERS: I bring it up for another reason. In your decision, you … said, “Congress has not acted to remove … baseball’s exemption from anti-trust, and Congress should do this.” Well, it went back to Congress: Congress never acted. The players finally forced the owners into an arbitration that resolved the issue without the Supreme Court having to pass on its constitutionality. And I’m wondering if there aren’t a lot of issues that come to you that you wish were resolved below the Hill, so to speak.

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: There are a lot of issues that we wish were resolved across the street … in the halls of Congress.

BILL MOYERS: Was there a constitutional principle that you invoked in sending it back to Congress? was it the separation of powers? Was it …

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: I think, the majority of us felt it was better that … Congress resolve this issue rather than we resolve it on some … constitutional basis that we might have to stretch for. Although, what they were arguing, actually, were the anti-trust provisions as statutory basis. And …

BILL MOYERS: Meaning?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: The … construction of the words of a statute that Congress has drafted and enacted … and trying to find out what Congress meant … So we don’t have a constitutional overtone, perhaps, in that case.

BILL MOYERS: Congress, often, does not know, itself, what it meant. When I was working as a young member of the Senate staff, I was amazed that, in the heat of debate or compromise, Congress would often pass a bill, and leave it for the courts to decide what Congress itself intended to do with that bill. It was a really … remarkable eye-opener, to me, when I was here.

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: I’ve had Congressmen make that very statement to me, that … I might meet them, somewhere, and joke, a little bit, about what they meant by a certain phrase in a certain statute, and it would be explained, it was the result of compromise. And so that … now, we’re in a situation where you fellows over in the Supreme Court can tell us what we meant.

BILL MOYERS: There’s very little, isn’t there, that is exempt from the Supreme Court, in our lives, today?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Sometimes, I think, we … we could scream at the cases that come to us, but it just … bearing … it bears out the old de Tocqueville admonition of years ago that, eventually, every social question, then, is made into the legal one, and comes before this Court. I wish it were otherwise, sometimes, but … that’s the way the system is, at the present time … It’s easier … when I was on the Court of Appeals, because … we could have a constitutional issue come up, and decide it, and there was always a certain amount of comfort in knowing that if we were wrong … as one of my colleagues put it, “Those … jokers down in Washington can … straighten us out.”

BILL MOYERS: This Court?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Yes. Yes …

BILL MOYERS: You’re now one of the jokers.

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: That’s right. (LAUGHTER)

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: And the buck has stopped here, and it … as a consequence, it’s a little harder.

BILL MOYERS: I never had thought about that. I guess, there was some consolation in being able, from the Appellate Court, to kick …

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Yeah.

BILL MOYERS: … the decision upstairs.

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: … And even if you were reversed, one didn’t mind too much. At least, it wasn’t the end of the line.

BILL MOYERS: Did that ever happen to you? Were you relieved, on some case, to be reversed by the Supreme Court?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Yes. Yes, indeed?

BILL MOYERS: Which case?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: A case called Alfred P. Mayer and Co. -I’ve forgotten the name of the other side — in which … I agonized, somewhat … ! wrote the opinion but felt we were bound by two opinions, up here.

BILL MOYERS:

By the Cour … Supreme Court?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: By the Supreme Court. That had been decided before then. And … much to my relief, when we were reversed, they overruled one of those cases. I think they should have overruled two, but … at least, they overruled one of them, which recognized, first, that … they had gone the other way, earlier. And … second, I like to think that we felt, properly, that we were bound by the earlier decision.

BILL MOYERS: In other words, you felt that you had to go along with the precedents that had been set in the cases before, but that it was still possible for the Court to set those aside. The Supreme Court.

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: In my writing, I, in effect, said that … That we hoped that the Supreme Court would take the case and, perhaps, rule the other way.

BILL MOYERS: Now, were they … were you teasing them into seeing it that way? …

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Oh, a little bit. (LAUGHTER) Of course.

BILL MOYERS:And they picked up on it.

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Yes. Yes … They were bound to. I think it was bound to come, and … of course, a real activist judge, in that position, would not feel bound. He’d go ahead and … decide the other way, and … in effect, tell the Supreme Court to go jump in the lake, and … but …

BILL MOYERS: But you were asking the Supreme Court to rescue you from the lake.

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Yes. Yes. Not, again, as matter of … personal philosophy, I suppose, should you … should you be bound, or should you go out in deep water by yourself.

BILL MOYERS: What you’re saying is that the six or seven thousand words in there leave a lot of ambiguity and … and … uncertainty, and that … trying to search for the Constitution is … is almost a daily affair on the lives … in the lives of judges: to decide what this document that’s two hundred years old really does mean.

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Well … I think that’s one of the beauties of the document is that it is not rigid. And … that’s why it’s lasted for two hundred years: it … it bends. But it’s flexible.

BILL MOYERS: Let’s just take a couple of the cases that you’ve had to wrestle with. Two years ago, the Court voted five to four, one vote, that federal wage and hour standards could apply to state and local government. Now, this overturned a decision of the Court in 1976, that upheld the states’ rights to regulate their own employees. You’d supported … you, Harry Blackmun, supported the 1976 law. But you changed your vote, in the second case, and that was enough to change federal law. Can you tell me why you changed your mind?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Well, of course, I was … rather the focus of concurrence, in the first case, which was Usury against The National League of Cities … I think, if one reads that concurrence, he will sense a certain amount of unease on my part … at that time.

BILL MOYERS: This is 1976. You weren’t quite sure …

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: 1976. But I went along with it, at that time. And, of course … I suspect that, when the other case came up, the Garcia against the … San Antonio Transit System … perhaps, by that time, I had become a little more … conscious of … what it was, in effect, a federal-state controversy, as to whether the federal rules should prevail over the state. And, of course, I’ve had criticism on that. I don’t feel that … I jumped the gun. I may have changed my mind. Some commentators have said this was a struggle for Blackmun’s mind, is what it was … (LAUGHTER) … because I was the … the awing-vote in both of them. But … and the petition for rehearing that was filed in the Garcia case is one of the … I thought it was almost slanderous, but then, that’s just my own opinion … along this line. But … Maybe one change a little bit as he grows. I … Potter Stewart, at one time … said that … and this is in a writing, in one of his short concurrences, that it’s better that wisdom comes late than not at all.

BILL MOYERS: What about the time the Court changed its mind in the course of one year? The majority of the Court said the public should be kept from attending criminal trials. You disagreed with the majority, and you dissented. But exactly a year later … in another case, the Court agreed overwhelmingly that the public did have a right to attend trials. But the Justices couldn’t even agree on why. The seven Justices in the majority wrote six different concurring opinions. Now, what was behind this involved and … difficult case?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: That was a freedom of the press case.

BILL MOYERS: Yes.

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: And … this is a very touchy … controversial area. The … words of the First Amendment are absolute: congress shall make no law affecting the freedom of the press. And … I think, all of us … grow. And … the cases come up … in a little different context. In the first one … according to one of the concurring opinions, it had to do only with pre-trial matters, and that the … the force of the amendment was applicable to trials. I was not in agreement with that, but I think it … it made a difference between the factual set-up of the two cases.

BILL MOYERS: Did the Court, in its second opinion, think it had made a mistake in its first one?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Well, one can read the second opinion to that effect.

BILL MOYERS: (LAUGHING) Yes … I did.

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: And not everyone would agree with it … But I

BILL MOYERS: The Court has subtle ways of admitting it … of taking itself back. (LAUGHS)

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Yes, and … seldom will it … will the … it admit error … It is always distinguishing … that it is perfectly obvious that the other case is distinguishable, when it isn’t obvious at all. And … sometimes, of course, the change in personnel is a factor. Sometimes.

BILL MOYERS: A Justice retires: a new Justice has …

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Yes.

BILL MOYERS: … a different perspective?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Sure.

BILL MOYERS: Different.

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: And a vote is different.

BILL MOYERS: What does it say about our understanding of the Constitution that the Court can change its mind a year later; can admit without really saying so that it made a mistake or that, in the case of the first decision … law can be made when a single judge changes his mind. What does it say about our understanding of the Constitution?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: We are fallible up here. And … mistakes … can be made. We try to make as few as possible … But even nine, as a group, can make a mistake … let alone one who changes his mind … switch a five-to-four into a four-to-five.

BILL MOYERS: There was a case, recently, in which you made it very clear that you thought the Court had made a terrible mistake. I’m speaking of Bowers versus Hardwick. The Court’s decision, in the words of the majority, that the Constitution does not confer on homosexuals a fundamental right to engage in sodomy. Actually, what the majority refused to strike down was a Georgia law that made sodomy … a crime.

BILL MOYERS: In 1982, a policeman knocked on the door of a house in Atlanta, Georgia, and asked if Michael Hardwick was home. He had a summons to serve for a previous offense. When the policeman was shown to Hardwick’s door, he walked in and found Hardwick in sexual activity with another man. They were arrested under a Georgia law which makes sodomy a crime. Hardwick was never brought to trial. But the State decided to test the law’s constitutionality with an appeal to the Supreme Court. Georgia Attorney General Michael Bowers.

MICHAEL BOWERS: Merely because something occurs within the privacy of the home does not immunize it from scrutiny by the law.

BILL MOYERS: On the steps of the Court, last year, attorney Lawrence Tribe stated the issue for his client, Michael Hardwick.

LAWRENCE TRIBE: The issue here is the more broad issue of the limitations on government power over the privacies of life in the home.

MICHAEL HARDWICK: I’m talking about an issue which is privacy. I’m talking about an issue which involves me and another consenting adult. Okay? Nobody’s being hurt. Okay? Nobody’s being endangered. I am not subjecting society or anyone else to it. Okay? It’s just a personal thing between me and this person. I am not committing a crime, as far as I’m concerned.

MICHAEL BOWERS: The interest, to me, is not so much in terms of what kind of conduct we are prohibiting, but where … are the confines of the Constitution in terms of proscribing what a state can do?

BILL MOYERS: Why did you disagree so strongly in that case that you took the unusual tact of reading your dissent from the bench?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Well, about once a year, a dissent is announced from the bench. I’ve had it done against me. It was done against me in Rowe against Wade. And … I can remember … Justices Black and Harlan doing this, on occasion. I felt strongly about that case, because I think the case was not as the majority described it. As you have just announced, I think, this was basically a case about privacy; privacy in the home. And that the principles of home privacy far exceeded the sodomous overtones of the case. It was five-to-four, and, of course, when one dissents, he always thinks he’s right, and, I think, on the broader base, that the dissent was correct. Whether it will ever be proved to be so, one doesn’t know. I think it will, in the long run.

BILL MOYERS: You think it will be overturned?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: I think it has to be overturned.

BILL MOYERS: Has to be?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Has to be … If we are to preserve … what we so value in this country, and that is, the privacy of the home.

BILL MOYERS: Even when the conduct there offends the sensibilities of the majority in the community?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Yes … I … susp … up to a point, now. one can’t say that, because a man kills his wife in the confines of a home, that he cannot be prosecuted. But …

BILL MOYERS: Where do you draw the line?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: … Well, Stanley against Georgia, a while back, which is before my time, also … I think … where the Court upheld the right to … possess … what were … were stipulated, as I recall, to be obscene films in the privacy of his home, could not be criminally prosecuted. Again, on privacy interests. And this goes back to the days of Brandeis and Warren, and … their concept about … a man’s home is his castle. I feel very strongly about it. All of us in the dissent felt strongly about it. But we … we felt, probably, that the … the majority of the … the Court was so … overcome with the sodomy aspect of it, which … that … it allowed its … judgment to be affected accordingly.

BILL MOYERS: Why do you think it was so obsessed with, as you said in your dissent … homosexuality?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Well … (LAUGHS) We were all brought up in a time, at our age, when this thing, this kind of thing ‘Was anathema, I suppose. And … Yet, here was a Georgia statute that was unenforced … and which the … representatives of the Georgia Attorney General’s Office, in effect, said, at oral argument, it won’t be enforced. What kind of a law is that?

BILL MOYERS: Why did the Court even take it up? The charges against Mr. Hardwick had been dropped. It was … wasn’t it a moot case? It wasn’t enforced. There was…

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: It … it came close to being a moot case, but it takes just four votes to take a case, here, not five, as you know. And … so, we had minority control of the calendar.

BILL MOYERS: Uh-huh. Was there any discussion that you could tell me about that would bring that to the agenda? was there some compelling reason? was it because of the political and social climate of the day … in which there is a resurgence of concern for morals, and family values, traditional values, so-called?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: I think, all of that, necessarily, enters into it, and … the … great emphasis on homosexuality, and the right of homosexuals, these days … I … I think itís one of those current problems that … not too long ago, used to be … brushed under the rug. But people are facing up to it now.

BILL MOYERS: You did a very interesting thing in your dissent. You quoted from that Stanley versus Georgia case that you … you mentioned, and you said something which compelled my attention, as I read it. Quote: “The makers of our Constitution undertook to secure conditions favorable to the pursuit of happiness. They recognized the significance of man’s spiritual nature, of his feelings and his intellect. They knew that only a part of the pain, pleasure and satisfactions of life are to be found in material things. They sought to protect Americans in their beliefs, thoughts, emotions and sensations.” The question is, what does that have to do with … with sodomy?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Well. Really defined … (LAUGHS) … It depends — in part, on how you define sodomy , I suppose, but … you know, for many people, the word sodomy is … is a term of anathema. After all, it’s named after the city of Sodom in the Biblical … tales about it. But I don’t want … myself … my philosophy is, and others disagree with this violently … I don’t want Big Brother in the bedrooms of America. We don’t like the knock on the door at night. That’s what the Fourth Amendment is all about.

BILL MOYERS: And if a law like this were to be enforced, it would call forth the Big Brother and the knocks in the night?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Well, I think so, myself.

BILL MOYERS: How would you enforce it, if, otherwise, you. couldn’t …

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: The cartoons that appeared all over the country, after Bowers against Hardwick came down … illustrated that very thing. Even… some of them had nine judicial-gowned members knocking on the bedroom door.

BILL MOYERS: You… you wrote, also, in there, that the fact that individuals define themselves in a significant way through their intimate sexual relationship with others, suggests there may be many right … and you put right in quotes … right ways of conducting those relationships, and that much of the richness of a relationship will come from the freedom an individual has to choose. You’re saying, are you not, that it’s up to two people to decide what is right for themselves, as long as it’s private, and … no one is injured?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: It comes close to saying that, doesn’t it? You have read this much more recently than I have. (MOYERS LAUGHS)

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: And much more thoroughly than I have … Of late, anyway.

BILL MOYERS: What do you think about Justice White’s argument, in the majority opinion, that law is constantly based on notions of morality?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: I would be distressed if our law were not … founded on principles of morality. Let … let me put it this way: There are some things that are legal but not moral. And there are some precepts of morality that are not illegal. One merely looks at the Tenth Commandment, and he sees that: Thou shalt not covet. It’s not anything illegal to covet something … We have no statutes that makes … covetousness a crime. But if one believes in the Ten Commandments … be shall not covet. So, I … as I say; I like to think of these as two large circles that … ninety-nine-percent, perhaps, over … overlap, and I think that’s part of the strength of our legal system. But there are some places where … law and morality are different.

BILL MOYERS: What is morally impermissible is not always legally wrong?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: That’s correct.

BILL MOYERS: A crime … a sin is not necessarily a crime?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: I think that’s correct.

BILL MOYERS: Because there are many people, who, for religious reasons, believe that homosexuality and, in particular, sodomy, are sins.

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Yes.

BILL MOYERS: In fact, Chief Justice … then Chief Justice Burger said, in his concurring opinion on this case, that condemnation of homosexual conduct is, quote, firmly rooted in Judeo-Christian moral and ethical standards. In the making of law, can you disregard the fact that… many religious groups consider sodomy a sin?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: No. He also said, however, that … it has been regarded … as anathema for millennia. And he … when he says that … whoever wrote that … doesn’t know … Greek history, I think.

BILL MOYERS: It was commonly practiced in …

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Very commonly practiced in Greek civilization.

BILL MOYERS: You grew up a Methodist, didn’t you?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Yes.

BILL MOYERS: Taught … probably, as I was a Baptist, that homosexuality was a sin.

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Oh, of course. Of course. Sure.

BILL MOYERS: Do you still believe that sodomy is immoral?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: … I supp … well, I haven’t … if you ask me directly, I suppose, I have to give you a … a positive answer to that…I…

BILL MOYERS: That you think it is … immoral?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: I would be distressed to see … my children indulge in it. But who am I to say that … people should not? I guess that’s a little difficult for me. I recognize my … limitations.

BILL MOYERS: But you’re a Supreme Court Justice: one of nine ultimate umpires. You can say what’s right or wrong.

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: … Well, I said what I thought was right or wrong in the dissent in Bowers.

BILL MOYERS: The Founders, obviously, didn’t challenge laws against sodomy. When they wrote this document, in fact, sodomy was a criminal offense … practiced … upheld … widely in Colonial America, and was forbidden by the law of the thirteen States when this Constitution was ratified. Why should the Constitution protect it now?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Well, this takes you, of course, into the current debate about … does the constitution … is it to be interpreted in the context of the times and atmosphere of 1787? I am one of those who feels … that … the privacy … concept has a Constitutional basis. And… maybe it’s attributable primarily to Justice Brandeis. I happen to think he was right.

BILL MOYERS: When he said?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: That the concept of privacy is basic to our law. And … from then on, I think, it began to emerge as a constitutional concept.

BILL MOYERS: Only in our time, in the last 25 years, has it … has it been enunciated, articulated~ so widely: in fact, the argument is, it’s not in the Constitution.

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Yes.

BILL MOYERS: That you can’t find the word privacy or even the concept of privacy.

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: That’s one of the great arguments that are made … that is made against the abortion decision. That a majority of the court, seven of us, went along with … finding it in the so-called “penumbras” of the Constitution.

BILL MOYERS: Penumbras meaning? Explain that to me.

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Well, penumbras, of course, as you know, is an astronomical term, emerging largely from eclipses of the sun and moon. But… as though it’s in the… the inner depths … of the wording of the Constitution, these broad phrases that … it may not be in … five or six words, but it certainly is implicit in the entire instrument, or in … portions of it.

BILL MOYERS: Well, now, tell me in Bowers versus Hardwick and Rowe versus Wade, where you find the root for privacy.

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Well, I found it in … as I think it was set forth in the Rowe opinion, primarily, in the preceding decisions here. Before my … one of them distinctly before ay time … Eisenstadt against Baird, and … and the Connecticut case. It seemed to me it was just a … a build-up that flowed as logically as … any development here.

BILL MOYERS: In the Connecticut case, the Court overturned a Connecticut law that banned … that outlawed the use of contraceptives.

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: It did, indeed. Even though administered and passed out by a licensed physician.

BILL MOYERS: And the Court was saying, “No Big Brother in the bedroom”?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Exactly.

BILL MOYERS: Right of privacy.

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Yes, sir … And that … those cases were on the books: that’s why I think maybe … Rowe against Wade as not such a revolutionary … opinion at the time. CLIP:

BILL MOYERS: But it was revolutionary to these people. In January, 1973, in Rowe versus Wade, the Supreme Court, by a seven-to-two vote, ruled that women have the right to a legal abortion.

PROTESTER: We want to show … our legislators, how much we object to the decision of the Supreme Court against … against children. It constitutes a war on children. (CROWD CHANT)

BILL MOYERS: Those who spoke for freedom of choice.

PROTESTER: … Denied, as a Roman Catholic woman, as a nun and an advocate of choice. (CROWD CHANT)

BILL MOYERS: Rove versus Wade has been the center of continuing controversy. Attorney General Edwin Meese has taken up the attack against it.

MR. MEESE: And if, in fact, the Justices of the Court find, as we … proclaim in our brief, that there’s no constitutional or legal doctrinal base for Rove against Wade, they can correct what we feel vas … an improper handling of the case. (CROWD NOISE UNDER)

BILL MOYERS: It took Justice Blackmun almost a year to write the opinion for the majority.

BILL MOYERS: Although seven Justices voted for that decision, the wrath came down on you.

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Well, there’s a lot of hate mail. It continues to this day. Of course, a good bit of it is organized. And … I understand that side of the question, I think. I understand why people feel so strongly about it.

BILL MOYERS: Why?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Well, I said so in the opening paragraphs of that decision, in 1973. Against the advice of Hugo Black, who was not around, any more, at that time, but … I think that vas the case to not heed his advice, and to express the … the difficulty of the issue.

BILL MOYERS: You expressed your anguish over the decision.

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Yes. sure. I wasn’t very pleased to have the … assignment come to me, but these cases come, we have to decide them. And someone has to write … an opinion, in … in a type of issue that the Court can’t win in the sense of having an opinion that is popular everywhere.

BILL MOYERS: Someone, not long ago, fired a shot through the window of your apartment. Your wife might have been in the line of fire, at a different moment. Somebody angry at … obviously, at your interpretation of the Constitution. Do you fear for your life? Are you constantly aware of that possibility?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: I don’t know about that … that shot. It vas … It’s about two years ago, now. And … and Dotty vas in the line of fire: had the … the bullet not been spent. It makes one wonder a little bit, sometimes, about what’s going on … But, at my age, I think, one’s expendable, and you … you carry on …

BILL MOYERS: Do you think it was deliberate?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: It … it might have been … I don’t know. It … it … could have been. Or it could have been just completely random.

BILL MOYERS: The case for abortion vas edging forward gradually … until this Court … this decision, the opinion you wrote, exploded in the public consciousness like a … bomb going off in the middle of a market. And, suddenly … there was organized and militant opposition against what was already happening quietly and slowly. Do you regret, maybe, having written that, and stirring up everybody?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: No, I have no regrets about it at all. It’s … It’s fourteen years ago, now … I might … today, write it a little differently, but … It was a Court decision; it was seven-to-two. Everybody says it’s a … H.A.B., a Blackmun opinion, of course. I get … that’s where I get the personal abuse. But there are others who’ve had … abuse on it. But … it was coming along. I think, probably … it achieved what would have taken a lot longer to achieve through other channels.

BILL MOYERS: Another intriguing aspect of the case is that the woman in question had already had the baby before the Court acted to concede her the right to an abortion. You didn’t have to make that decision at that moment, did you? You could have waved past; moved on.

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Well, that was the kind of situation, however, where … the period of gestation is so short that this will happen with every case, before it ever gets up here … And …

BILL MOYERS: So there was something more than the individual in this case?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Oh, yes, indeed.

BILL MOYERS: What was it?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: More than that particular individual, but there are … many, many others, out there, too.

BILL MOYERS: How much were you influenced in your feelings about women? Including the Rowe versus Wade decision … permitting abortions … by the fact that you not only have a wife, but three daughters? There are four …

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: And a female puppy, at the time.

BILL MOYERS: A female puppy … (LAUGHS) … at the time. HOW much did that circle of encasement influence your judgment on the Court?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: … I … I can say that having three daughters was not an influence. There are those, of course, who won’t believe me, but … (MOYERS LAUGHS} … and say definitely they were.

BILL MOYERS: Do you ever really know from what ultimate source your final opinion arises?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: I think it … I think one has to say that it just comes from one’s exercise, as best he can, of the judgment that he possesses. But, in some respects, I think … judges are appointed … federal judges are appointed … in theory, because … of the appointing authority having confidence in their good judgment. That used to be … I … i had thought, when I was a youngster, that … that used to be the criterion by which people in Congress were voted. Were elected. Not on a single issue, here or there, but because people … elected them by having confidence in their basic good judgment when faced with facts that the entire public … often … are not faced with. But … that’s why I get disturbed when I see single issue campaigns.

BILL MOYERS: People who say that everything depends on one Issue?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Yes, exactly. Exactly.

BILL MOYERS: And that’s certainly happened in the abortion case.

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Yes. Yes. It’s been attacked from many quarters and for many reasons.

BILL MOYERS: You say that we are a society evolving … legally … and morally … scientifically. do you think Rove versus Wade will be affected when medical technology permits the preservation of very young fetuses outside the womb? How

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Well, it’ll be affected somewhat. I stated that, as of now, the point of viability vas twenty-six weeks … This is being pushed back. And … this is a medical advance, but these are evolving facts, and we’ll take another look at it when the time comes. One of the recent dissents says that Rove against Wade is on a collision course with itself. I don’t buy that. But … and I think there’s flexibility enough in Rove against Wade to meet that issue when it arises.

BILL MOYERS: This Court is moving to the right.

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Yes, indeed, it is.

BILL MOYERS: Does that concern you?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Well … nothing I can do about it. But … the pendulum swings back and forth.

BILL MOYERS: Some people, Mr. Justice, are saying that the Court’s decision in the sodomy case we were talking about is the first step toward limiting the right of privacy that you used in the abortion decision, that the Court, now, with a conservative sway, is about to start taking back the right of privacy, end, ultimately, will move toward declaring Rove versus Wade invalid. Do you think that Rove versus Wade stands the chance of being overturned?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Oh, I think any case up here always stands a chance of being overturned. I can’t forecast that one way or another. It … it may well be overruled. It’ll … that will depend primarily on the personnel of the Court. I think. But … it has stood for … fourteen years, now. I think it is a landmark decision … along the road that we must take toward the emancipation of women … And I make no apology for that whatsoever.

BILL MOYERS: Why do you feel so strongly about that?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: I think it’s long overdue.

BILL MOYERS: … You don’t feel that women have equality before the law? Equality in society? You use the word “emancipation.”

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Well, I think, the … history of women would Indicate that they have not had it completely. Now, I’m not a … I’ m not a great feminist, in the sense that some people are, but … in many ways, our history tells us, they’ve been second-rate citizens.

BILL MOYERS: Well, the document denied them enfranchisement and sufferance …

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Indeed it did.

BILL MOYERS: For long, as it did blacks and Indians. I mean, when people talk about venerating this document, or even saying what ain’t broke, it sure was broke for a long time, as far as Indians, who were eliminated while this Constitution vas in force; blacks who were subjugated under this Constitution; and women, who were denied enfranchisement under this Constitution.

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: Correct … under this Constitution.

BILL MOYERS: … What does that say to you about … our system?

JUSTICE BLACKMUN: I think it says to us … it has to say to us that we are a developing … nation, a developing system; that things can be bettered, and that we’d better be on the road to make it better. We have a lot of black pages in our history … we haven’t been perfect; that Constitution hasn’t been perfect. But … I think, we’re on the road to making it better.

BILL MOYERS: Supreme Court Justice Harry Blackmun In Search of the Constitution. I’m Bill Moyers.

This transcript was entered on March 30, 2015.