The New York Times’ David Leonhardt is one of the country’s most thoughtful commentators on the links between economics and politics. So when he writes an article entitled “Inequality Has Actually Not Risen Since the Financial Crisis” people notice. In this case, it was conservative commentators who paid the most attention, trumpeting his piece as akin to a climate scientist admitting that global warming isn’t happening. “Anyone who claims to see a continuous upward trend in top 1 percent incomes isn’t looking at the right data,” wrote the Cato Institute’s Alan Reynolds.

But let’s continue the analogy to global warming. Just as a freak cold year shouldn’t blind us to the long-term warming of the planet, the temporary decline of incomes at the top because of the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression shouldn’t blind us to the equally clear long-term rise in the share of national income going to the very top.

In fact, as Leonhardt quickly noted in his piece, steep recessions — especially financially driven ones — generally hit the incomes of those at the top particularly hard. Of course the rich can afford such reversals the most; the true suffering falls on those near the bottom rather than at the top. Still, it is important to recognize that in relative terms the rich actually lost ground when the crisis hit. Nor was this unusual: Thomas Piketty showed in his magisterial examination of much longer trends in income distribution that economic crises and wars can be devastating to the wealthy. Top 1 percent incomes consist substantially of income from capital, which is much more volatile than wages and salaries and can be devastated by major financial crises and wartime destruction of physical and financial assets.

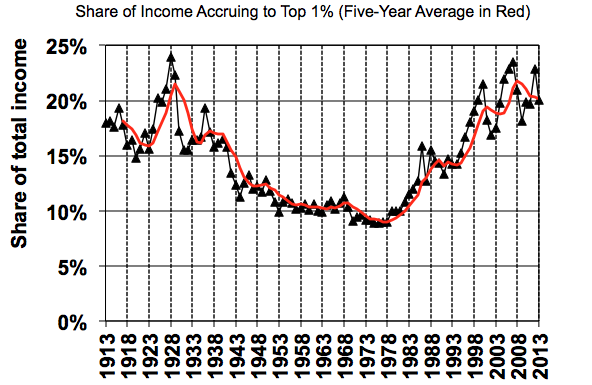

Since the financial crisis, however, the share of income going to the rich has come roaring back, as it did after the (much smaller) 2001 and 1987 market reversals. As the figure below shows, the share of income accruing to the top 1 percent is still twice as high as it was in the late 1970s, a trend that is undeniable when you smooth the data by averaging across five years.

This chart has been updated to include 2013 data. (Chart: The Evolution of Top Incomes in the United States.)

Moreover, just as we now know that greenhouse gases emitted by human societies are the major contributor to global warming, we also have clear evidence that US government policy is a major reason why the United States is the most unequal rich democracy in the world. This, in fact, is the real point of Leonhardt’s article, even if most of its celebrants seemed to miss it: government policy played a crucial role in (temporarily) halting the growth of inequality. In particular, reforms pushed by the Obama administration, backed by Democrats in Congress — and furiously opposed by Republicans — made meaningful contributions to expanding economic security and opportunity for both poor and middle class Americans. Not incidentally, the Obama administration also rescued the financial sector, softening the blow for both the affluent and the poor.

Measures to directly aid low- and middle-income workers hardly represent the massive expansion of government against which the administration’s critics rail. Nonetheless, unemployment insurance was expanded and extended during the downturn, and payroll taxes (which hit less affluent workers harder than income taxes) were temporarily cut. More important, though we won’t much see the effects in household income data, the Affordable Care Act extended insurance protections particularly beneficial to the low-wage workers most likely to lack secure coverage. These expansions were financed partly through slowdowns in the growth of health spending and partly through progressive taxation. The message, which Leonhardt appropriately stresses, is clear and vital: Ever-rising inequality is not inevitable; it can be fought effectively through thoughtful and vigorous public policy.

Here, however, is where Leonhardt’s account falls silent too quickly. It is not just that the initiatives of 2009-10 were too modest. It is also that they came to an abrupt halt and, indeed, policy has moved mostly in reverse since the election of 2010. Republicans and much of the business community have mobilized to limit or claw back vital policy reforms. Even “moderate” economic elites successfully urged a premature shift away from concerns about employment and opportunity to a fixation on deficit reduction — a fixation that seems more preoccupied with cutting vital programs for the middle class, such as Social Security, than with actually assuring the nation’s long-term fiscal health. Meanwhile, conservative judges have blocked or gutted important reforms and currently threaten the Affordable Care Act, the most significant public policy diminishing inequality in the past half-century. Today, despite much talk about helping the middle class, there is no meaningful prospect for measures that would significantly reduce inequality in the short to medium term.

So Leonhardt is correct that too many on both the left and right treat rising inequality as unstoppable. Government policy can make a difference, and it already has. But given how little has been done since 2010, the most important message we need to hear today isn’t that government did a lot during the crisis, but that it needs to do much more right now. Moreover, though Leonhardt implies that government action is all about redistributing income from the top toward the bottom, most of the things government should do right now would be growth-promoting as well. More vigorous reform of our staggeringly inefficient health care system, for instance, would be good for everyone except those health care providers extracting “rents” from the rest of us, even as it reduced inequality. The same would be true for more thorough-going financial reform. And investments in R&D, in college and pre-school education for those least able to access such education, and in improved public health — all would have huge payoffs for our society while also reducing inequality.

Rising inequality is no more natural than global warming. And just as with global warming, our biggest fear should be that it becomes increasingly self-reinforcing — not because of some “natural” economic process, but because economic power begets political power, which can be used to further increase economic advantage. Look around, and the evidence that this is a real threat abounds. To cite just one example of many, the Koch brothers network, led by businessmen who are committed libertarians opposed to any effort to reduce inequality, are planning to spend almost $1 billion in next year’s election.

In other words, read beneath the headline of Leonhardt’s article and you have an argument for greater alarm about the toxic relationship between rising inequality and the dysfunction of the federal government — a message exactly opposite of the one that the inequality deniers want to hear.

The views expressed in this post are the author’s alone, and presented here to offer a variety of perspectives to our readers.