Over the last week and a half or so, in Washington especially but here in New York City, too, much has been written about the turmoil at The New Republic magazine after the resignation of editor Franklin Foer was followed by the public hari-kari of several other editors and writers. They left in support of Foer against owner Chris Hughes, the Facebook co-founder and multimillionaire who bought the magazine in 2012. After promises of maintaining intellectual rigor and integrity at the publication, Hughes recently brought in a new CEO who announced he would be “re-imagining TNR as a vertically integrated digital media company.”

There will now be a pause as many of you say to yourselves, “Who cares?” And given the course of human events and a world filled with terrifying tumult, to a degree you’d be right. Also, in the interest of full disclosure, I probably should mention that as a callow college freshman I worked for The New Republic as a copyboy whose main duties were running the occasional errand and compiling the magazine’s semi-annual index, a time-consuming task that in those pre-computer days required a typewriter, index cards, tape and sheets of legal paper. In alphabetical order, the cards were attached to paper with tape and sent off to the printer, a Mr. Gutenberg, I believe.

In those days the magazine functioned with just a handful of full-time employees from its townhouse off Dupont Circle in DC, the physical atmosphere musty with age like your grandparents’ house and emotionally musty with memories of Woodrow Wilson, FDR and Adlai Stevenson.

Seismic changes began in 1974, long after I was gone, when TNR was taken over by publisher Marty Peretz. Since then, the magazine has undergone a series of publishers, editors and contributors as well as fierce ideological, sociological controversies — remember its publication of excerpts from Charles Murray’s The Bell Curve? — not to mention the Stephen Glass plagiarism scandal and bitter infighting leading right up to the current mess.

So maybe why you should care is because the magazine, despite its smallish circulation, has often paralleled the country’s miseries, while at the same time churned the national conversation. Right or wrong, it has had an impact and is read by people whose opinions and actions have an effect on decision-making in government and politics. Which is why earlier this week we reprinted Robert Parry’s essay, “The New Republic’s Ugly Reality,” and why we point you now to Moyers & Company guest Ta-Nehisi Coates’ December 9 article at The Atlantic, “The New Republic: An Appreciation.”

He writes:

TNR had a hand in the careers of an outsized number of prominent narrative and opinion journalists. I have never quite been able to judge the effect of literature or journalism on policy, but I know that in my field, if you had dreams of having a career, you had to contend with TNR. My first editor at The Atlantic came from TNR, as did the editor of the entire magazine. More than any other writer, TNR alum Andrew Sullivan taught me how to think publicly. More than any other opinion writer, Hendrik Hertzberg taught me how to write with “thickness,” as I once heard him say. A semester in my nonfiction class is never quite complete without this piece by Michael Kinsley. TNR’s legacy is so significant that I could never have avoided being drawn into the magazine’s orbit. Even if I had wanted to.

But, Coates continues, “…if one were to attempt to capture the ‘spirit’ of TNR, it would be impossible to avoid the conclusion that black lives don’t matter much at all… I spent the weekend calling around and talking to people who worked in the offices over the years. From what I can tell, in that period, TNR had a total of two black people on staff as writers or editors. When I asked former employees whether they ever looked around and wondered why the newsroom was so white, the answers ranged from ‘not really’ to ‘not often enough.’”

… White people are often sincerely and greatly pained by racism, but rarely are they pained enough. That is not true because they are white, but because they are human. I know this, too well. Still, as of last week there were still no black writers on TNR’s staff, and only one on its masthead. Magazines, in general, have an awful record on diversity. But if TNR’s influence and importance was as outsized as its advocates claim, then the import of its racist legacy is outsized in the same measure. One cannot sincerely partake in heritage à la carte.

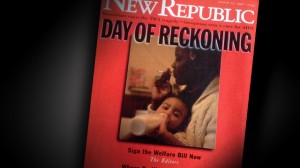

… When I examine the magazine’s archives, I am not so much angry as I am sad. There really was so much fine writing in its pages. But all my life I have had to take lessons from people who, in some profound way, cannot see me. TNR billed itself as the magazine for iconoclasts. But its iconoclasm ended exactly where everyone else’s does — at 110th Street. Worse, TNR encouraged incuriosity about what lay beyond the barrier. It told its readers that my world was welfare cheats, affirmative-action babies, and Jesse Jackson. And that white people — or any people –would be urged to such ignorance by their Harvard-bred intellectual leadership is deeply sad.

You can read Ta-Nehisi Coates’ complete article at The Atlantic.